“In this Viewpoint, we question traditional approaches to teaching clinical reasoning that focus primarily on illness scripts and pattern recognition. We argue that, while pattern recognition comes naturally to humans, it is susceptible to cognitive biases that lead to diagnostic errors. Instead of emphasizing illness scripts, educators should aim to enhance diagnostic acumen by teaching learners to engage in critical thinking—in other words, reasoning from foundational principles of human pathophysiology. The importance of moving beyond pattern recognition will become increasingly urgent as generative artificial intelligence (AI) becomes central to the practice of medicine.

Illness Scripts: Fast, but Risky

As the first step in clinical reasoning, the educator traditionally exhorts the trainee to generate a differential diagnosis based on a patient’s clinical presentation and laboratory data. The trainee prioritizes these diagnoses based on how closely the illness script for each diagnosis matches the patient’s presentation. Through deliberative practice, trainees build their repositories of illness scripts and learn to sift through them rapidly when presented with a new patient.

This approach to clinical reasoning relies on cognitive processes that are optimized for pattern recognition (ie, system 1 thinking),3 making it fast and practical for situations in which a patient’s presentation matches a clinician’s illness script. The problem is that fast, pattern-oriented thought processes are susceptible to well-defined cognitive biases. When a patient’s presentation does not match a prototypical illness script or when conflicting information subsequently arises, these cognitive biases can compromise clinical reasoning and lead to diagnostic errors.

One example of cognitive bias is premature closure—the tendency to finalize a diagnosis early and close one’s mind to other possibilities. For instance, while experienced clinicians typically outperform trainees in diagnostic accuracy, these groups perform similarly when discordant information is presented partway through a case, suggesting that clinicians are reluctant to revise their initial impressions once formed. Another bias is anchoring on a certain aspect of a case early in the workup. For example, in 1 study of more than 100 000 patients with a history of heart failure who presented to the emergency department with dyspnea, the mere mention of heart failure in the triage note was associated with delayed and missed diagnoses of pulmonary embolism.

Approaches to clinical reasoning based heavily on illness scripts can be thought of as cultivating routine expertise. Routine experts have large repositories of illness scripts on which to draw when evaluating patients, making them efficient and reliable in many clinical scenarios. However, when confronted with a new problem, routine experts attempt to adapt the problem to solutions with which they are comfortable rather than flexibly creating solutions that better match the problem. This means that even when a patient’s presentation does not fully match an illness script, a routine expert will default to pattern-oriented thought processes, increasing the likelihood of a diagnostic error.

Moving Beyond Illness Scripts

Unlike routine experts, adaptive experts use unfamiliar problems as opportunities to consider new, potentially superior solutions. Adaptive expertise involves cognitive processes that are better suited to exploration and analysis (ie, system 2 thinking), trading speed for flexibility and accuracy.

Educators can cultivate adaptive expertise by focusing less on pattern recognition and more on teaching learners to engage in critical thinking, starting from foundational principles of human biology and pathophysiology. In particular, instead of asking trainees to move directly from a patient’s clinical presentation to differential diagnoses, educators can push trainees to develop testable, intermediate hypotheses that explain a patient’s presentation in terms of pathophysiological processes.

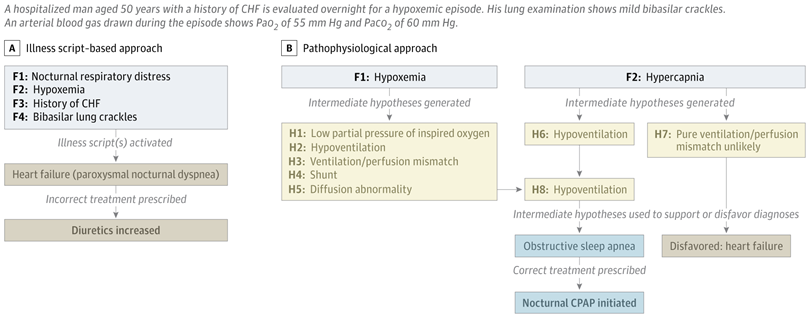

For example, when evaluating a patient with peripheral edema and shortness of breath, a trainee should be taught to avoid jumping directly to a potential diagnosis that matches an illness script (eg, heart failure). Instead, the trainee might consider pathophysiological causes of edema (eg, high capillary hydrostatic pressure, low capillary oncotic pressure, reduced lymphatic drainage, increased capillary permeability), develop an intermediate hypothesis regarding which causes are relevant to the patient, and gather data (eg, jugular venous pressure, serum albumin) to test these hypotheses. The process of developing and iterating on these intermediate hypotheses before connecting them with provisional diagnoses requires deliberative analysis, reducing the tendency to force a patient’s presentation into the shape of an illness script and reducing the cognitive biases associated with doing so (Figure).

Optimal clinical reasoning will involve an appropriate balance between illness scripts and pathophysiological reasoning. In our view, medical education has historically overemphasized the former—to which learners are predisposed even without explicit teaching—and underemphasized the latter. The risks of this historical approach will become even more salient as generative AI, especially in the form of large language models, assumes a greater role in clinical evaluation and diagnosis.

AI excels at pattern recognition. As large language models and their training data improve, AI will likely outperform human diagnosticians, especially in routine cases that cohere with prototypical illness scripts. Human physicians should develop complementary skills that machines can less easily replicate, such as flexible reasoning, creative problem-solving, and the ability to navigate uncertainty in cases involving new knowledge and/or unfamiliar presentations. To the extent that medicine represents a “wicked” environment—marked by complexity, incomplete rules, and delayed or inaccurate feedback—it is less amenable to AI, suggesting that efforts to teach clinical reasoning should prioritize flexibility and nuance over automaticity.

Now more than ever physicians must build their practices on the foundation of strong critical thinking skills. In the 21st century, this means medical education must go beyond teaching students what to think and instead teach students how to think when patterns do not fit (or how to verify when patterns do seem to fit). By questioning a primary focus on illness scripts, emphasizing pathophysiological reasoning, and cultivating adaptive expertise, we can prepare future physicians—and their patients—for what may lie ahead.”

Full article, RM Schwartzstein and AA Iyer, JAMA, 2025.9.25