“[Introduction] Despite spending more than any country in the world on health care, life expectancy in the US is comparably worse than that of most other high-income countries and declining both in absolute value and relative rank. However, life expectancy across US states varies just as markedly as it does across high-income countries, from 81.8 years in Hawaiʻi to 74.7 years in Mississippi in 2019—a divergence that has been increasing over time. US states vary considerably on policy decisions related to the spending, regulation, and provision of health care; reproductive health; tax policy; social welfare programs; and in relation to crime, poverty, income, and other social determinants of health. These differences have increased in the past decade, as major legislation related to social welfare and health care coverage—such as Medicaid expansion or, more recently, abortion rights—are determined at the state level.

[..] Avoidable mortality is a population health measure that tallies the number of deaths each year in the population younger than 75 years that could have been prevented or avoided through timely and effective health care and prevention. This metric is commonly used by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the European Union (EU), and several nations to evaluate the performance of health systems. Avoidable mortality can further be divided into preventable and treatable mortality. Preventable mortality is defined as deaths that may be avoided with effective prevention practices, including through public health and health promotion practices. Examples include vaccine-preventable deaths and road traffic collisions. Treatable mortality is defined as deaths that may be avoided with timely and effective medical care. Examples include deaths from appendicitis or sepsis. Some deaths are considered both preventable and treatable (eg, deaths from cervical cancer, ischemic heart disease, and tuberculosis). In these cases, the death is split so that a proportion is allocated to both categories. Some comparative studies have examined avoidable mortality across high-income countries, including the US; however, these predate the years of declining US life expectancy beginning in 2014. Other cross-sectional studies have shown variation across US states, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, but not in relation to other countries. To the study investigators’ knowledge, there is limited evidence examining how US states compare with other high-income countries on avoidable mortality over the past decade. [..]

[Methods] Mortality data for countries between 2009 and 2021 were obtained from the WHO Mortality Database. WHO mortality data categorize death counts according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) chapters by country, year, age group, and sex. [..]

Mortality data for US states between 2009 and 2021 were obtained from the CDC National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) Multiple Cause of Death restricted-use micro-data files. [..]

We used population data to calculate mortality rates within countries and US states. Country midyear population estimates by single year of age and sex are from the US Census Bureau International Database Time Series (1960-2023)23 and from the CDC WONDER Bridged-Race Population Estimates (1990-2020) and Single-Race Population Estimates (2020-2022) for US states.

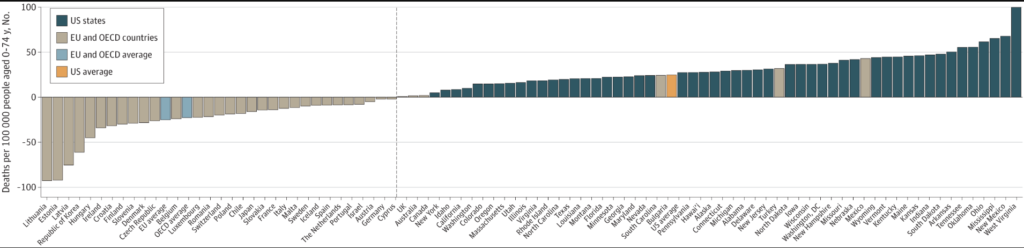

[Results] [Between 2009 and 2019] On average, mean (SD) avoidable mortality increased by 32.5 (18.0) avoidable deaths per 100 000 across the US, although this varied considerably by state, ranging from 4.9 in New York State to 99.6 in West Virginia. In contrast, median (IQR) avoidable mortality decreased in most comparator countries (−14.4 [−28.4 to −8.0]), except for Mexico, Turkey, Bulgaria, Canada, Australia, and the UK. EU countries experienced a mean (SD) decrease of 23.9 (29.5) avoidable deaths per 100 000, and OECD countries an average decrease of 19.1 (29.5). Only the 22 states with the greatest increases between 2009 and 2019 increased significantly. [..]

In the US, most of the increase in the 2009 to 2019 period was in preventable mortality (preventable change 2009-2019: median [IQR], 24.3 [15.5 to 32.1] preventable deaths per 100 000; treatable change 2009-2019: 7.5 [3.4 to 10.2] treatable deaths per 100 000). Avoidable mortality in US states between 2009 and 2019 was mostly due to increased avoidable deaths from external causes (eg, traffic collisions, homicides, suicides, and drug- and alcohol-related deaths; median [IQR], 15.0 [9.4 to 20.3] deaths per 100 000), which were mainly preventable. Drug-related deaths were also the main driver of increased avoidable deaths from external causes in the US from 2009 to 2019, contributing 71.1% of the increase. To a lesser extent, avoidable deaths due to circulatory and respiratory diseases and cancer increased in most states. Notably, most states experienced an increase in treatable mortality related to neoplasms (median [IQR], 0.4 [−0.3 to 1.2]), with few exceptions. However, in most instances, this increase was offset by gains made in preventable mortality for neoplasms (median [IQR], −4.4 [−5.9 to −1.6]), so improvements in avoidable mortality due to neoplasms seemed to be mostly from cancers disposed to prevention.

Conversely, most comparator countries made gains in avoidable mortality, predominantly driven by improvements in preventable mortality (median [IQR], −10.6 [−18.0 to −3.3]) and to a lesser extent in treatable mortality (−3.8 [−11.0 to −1.9]). Avoidable deaths from external causes declined in nearly every country except Canada, Turkey, the UK, Mexico, the Netherlands, Australia, and Iceland (median [IQR], −6.1 [−10.5 to −1.8] avoidable deaths per 100 000). Avoidable deaths due to circulatory and respiratory diseases and cancer also declined. Several countries experienced small increases in preventable mortality from respiratory illnesses (median [IQR], 1.2 [0.8 to 2.3] preventable deaths per 100 000).

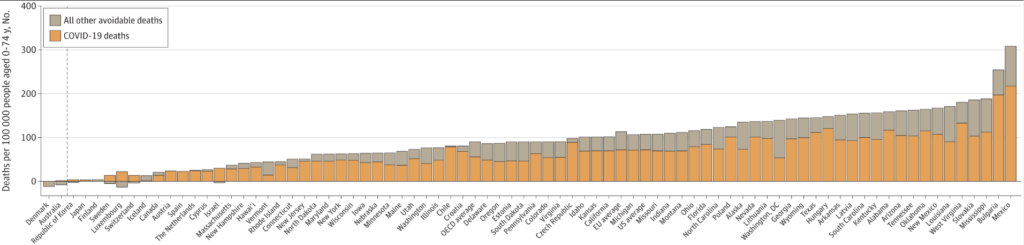

Between 2019 and 2021, avoidable mortality increased for all US states and nearly all comparator countries, except for Denmark and Australia. This was driven predominately by COVID-19 deaths, which the OECD/Eurostat list classified as preventable. The rate of avoidable deaths from circulatory system diseases and external causes increased for most states and countries, and treatable mortality gains were offset by preventable mortality increases, which included COVID-19 deaths, for most geographies. Between 2019 and 2021, comparator countries still fared much better than most US states. Avoidable mortality increased significantly for almost all US states from 2019 to 2021, with only some northeastern states (Vermont, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts) and Hawaiʻi as exceptions. Conversely, only some Eastern European countries and Chile experienced a significant increase in avoidable mortality over the same period. The magnitude of increase in avoidable deaths across states and countries between 2019 and 2021 was strongly associated with baseline avoidable mortality (Pearson ρ = 0.86; P < .001).

[Discussion] Despite spending more on health care than every other high-income country, the US had comparably higher avoidable mortality, which includes deaths that can be avoided through timely prevention and access to high-quality health care. This study, which disaggregated US mortality rates across individual states and 40 EU and OECD countries, observed 5 key findings.

First, between 2009 and 2019, avoidable mortality increased in all US states, while decreasing in most comparator countries. The increase in US states was observed in both preventable and treatable mortality, with external causes of death and circulatory system diseases contributing the most. The stark contrast in prepandemic trends in US states vs comparator countries suggests that there are concerning broad and systemic issues at play.

Second, from 2009 to 2019, the study observed variation in avoidable mortality widening across US states and narrowing in comparator countries. Among comparator countries, those in Eastern Europe improved significantly, albeit having the highest rates of avoidable mortality at baseline in 2009. While the study was unable to determine what accounted for these differences, there were many changes in the policy landscape across these regions that warrant further investigation, such as accession of countries to the EU, which may have led to more policy convergence, particularly around social and economic policies. Conversely, in the US, the growing heterogeneity of state-level policy decisions across this period could have differentially impacted avoidable mortality across states (eg, adoption of Medicaid expansion across states and growing divergence in other areas, such as abortion rights, firearm legislation, and public welfare benefits).

Third, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, all countries experienced an increase in avoidable mortality between 2019 and 2021, reversing the downward trend observed in the prior decade. However, US states still fared worse than most of the observed countries. In US states, avoidable mortality continued its upward trend, albeit at a higher relative increase from the trend in the prior decade, and only some northeastern states and Hawaiʻi had insignificant increases. During this time, avoidable mortality significantly increased for only some Eastern European countries and Chile. The greatest increases in avoidable mortality were also observed in countries and states with higher baseline avoidable mortality, which could indicate that the prior performance of a state or country on population health is associated with its capacity to respond to health care shocks or emergencies. Increases in avoidable mortality, while mostly related to COVID-19 deaths, also occurred in deaths from other causes. This could represent some combination of factors, including (1) a continuation or exacerbation of a secular trend in avoidable deaths preceding the pandemic (eg, in overdose deaths, which increased between 2020-2021), (2) an increase in non–COVID-19 deaths related to disruptions in health service delivery, or (3) an increase in COVID-19 deaths miscoded as other deaths. More work should investigate the extent to which differences in underlying demographics, especially socioeconomic status and the adoption of social and health policies across states and countries, influenced the observed population health outcomes during this period.

Fourth, avoidable mortality in the US appears to have been disproportionately driven by preventable mortality, which is influenced by socioeconomic factors and public health policy. This underscores the necessity for a multisectoral approach to improve US population health. For example, policies promoting access to healthy foods, limiting exposure to harmful products, and combating obesity can significantly reduce the risk and incidence of chronic diseases. Legislative measures addressing gun violence can lower injury-related deaths. Regulations on motor vehicle safety can prevent collisions and deaths. These broader determinants of health require coordinated efforts across various sectors and highlight that improvements in preventable mortality can extend far beyond the realm of clinical care.

Fifth, the study observed a consistent, negative, and significant association between health spending and avoidable mortality for comparator countries, but no statistically significant association within US states. While the analysis cannot say anything about the direction of the association, several other studies have shown that higher health spending in the US is likely the product of higher prices, which might explain why the study did not observe greater expenditures to be associated with lower avoidable mortality rates. However, this could also indicate that the US spends more because its population is sicker. While the study cannot determine the underlying mechanisms, the lack of a significant association between health spending and health care outcomes in the US raises questions about the US health care system’s overall efficiency.

This study adds to a growing literature examining the comparative position of US mortality with regard to other countries by broadening the outcomes compared to focus on conditions amenable to health treatment and prevention. The study also extended the comparison to include US states, rather than the US as a whole, better capturing the heterogeneity of outcomes within the country and building on reports that have examined this cross-sectionally. Finally, this article explores trends in the pre–COVID-19 and COVID-19 periods, illustrating the variability that exists across these periods. Study findings highlight the influence state-level policies may have on population health within the US.”

Full article, I Papanicolas, M Niksch and JF Figueroa, JAMA Internal Medicine, 2025.3.24