“Empirical evaluations of state vaccination exemption laws lead to 4 conclusions. First, states without nonmedical exemptions have lower rates of vaccination exemptions and vaccine-preventable diseases than states that permit religious and/or philosophical objections. Second, the ease with which an exemption may be obtained (for example, the paperwork and effort involved) is associated with state exemption rates as well as disease outbreak risk.

Third, reductions in exemption rates that look small in terms of percentages can pack a real public health punch. Based on Delamater and colleagues’ projected school enrollment data for 2027, the estimated decrease in exemptions from 2.59% to 1.41% in California means that nearly 84 000 fewer children will fall short of being up-to-date on their immunizations that year. Further, the gains are not evenly distributed: Areas of California with the highest exemption rates before SB277’s passage saw the largest reductions after the law was implemented. Because a quarter of California’s kindergartens previously had exemption rates that were high enough for herd immunity against highly infectious diseases, such as measles, to be compromised, such distributional effects are important.

Finally, California’s experience suggests that if the law leaves open avenues for avoiding immunizations, parents who are opposed to vaccines will find a way to take them.

Avoiding repeated skirmishes requires getting it right the first time. Laws narrowing vaccination exemptions should include 5 key provisions. First, they should require that medical exemptions come from a pediatrician or family physician whom the child sees for regular care. Second, they should limit the justifications for medical exemptions to valid, recognized contraindications to immunization. Third, they should provide for review of medical exemptions by the department of health, as well as action against physicians who do not provide a specific and valid clinical rationale. Fourth, they should clearly task the department of health, not schools, with reviewing exemptions. Finally, they should avoid grandfather clauses. Other states can also learn from what California did right: jettisoning personal belief exemptions of all kinds, applying the rules to private schools and day care centers as well as public ones, setting forth a specific but expansive list of required immunizations, and making annual data on school-level exemption rates public.”

Narrowing Vaccination Exemption Laws: Lessons From California and Beyond (2019.11.5)

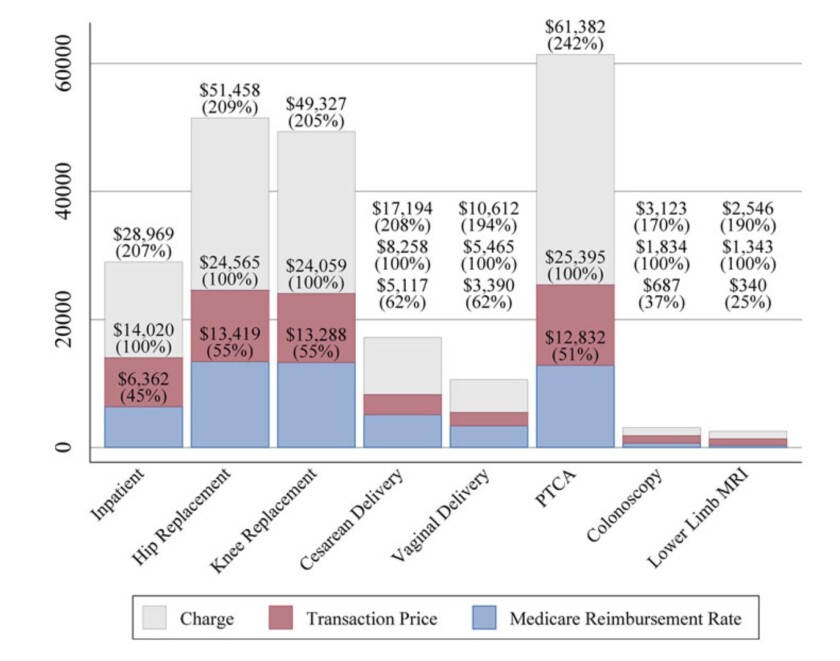

“In the article, Reinhardt and his co-authors explained that although Americans had fewer hospital admissions per capita and shorter stays per admission than residents of other countries, they paid more per admission and per day. The U.S. also paid the highest prices, by far, for drugs.

The culprit was the private insurance sector, which played a much larger role in America than in other countries; the public sector, represented here mostly by Medicare and Medicaid, was roughly as cost-effective as public health programs elsewhere.

Yet “Priced Out” raises an even more important point — that a chief obstacle to enacting sensible healthcare reform in the U.S. is our refusal to state the political issue squarely. As Reinhardt writes, it’s this: “To what extent should the better-off members of society be their poorer and sick brothers’ and sisters’ keepers in health care?”

To Reinhardt, this question is “the elephant in the room no one likes to mention.” Although it’s the fundamental ethical question underlying the healthcare debate, “we have never been able to reach a politically dominant consensus on the distributive social ethic that should guide our health system, because we dare not confront that question at all.”

Every other developed country has long since pondered this fundamental question and concluded that healthcare is a social good that should be “available to all on roughly equal terms,” Reinhardt writes, though the method of delivery varies from country to country.

Instead, we’re distracted into addressing the question in what Reinhardt calls “camouflaged form”— whether to “repeal and replace Obamacare,” for example or whether to allow premiums for seniors to be five times higher than for young adults, or three times higher.

Figure caption. The prices, stupid: Hospitals set putative list prices for procedures (gray), but the real charges are negotiated with private insurers (red), which are in turn higher than Medicare rates (blue). “PTCA” signifies a routine cardiac angioplasty.(Health Care Pricing Project)

Variations like this make a mockery of the conservative mantra that the key to lowering healthcare spending is to give patients more “skin in the game” via higher deductibles and co-pays. The idea that this will prompt patients to shop around for the best deals “has been a cruel hoax,” Reinhardt writes.

[..] Reinhardt attributes much of the difference to the insane administrative complexity of the American system, especially in the private sector. The costs are manifest. U.S. physician practices spent an average of more than $80,000 per doctor interacting with health insurers, according to a 2011 study. That was four times the cost incurred by practices in Canada, which has a single-payer system. As Reinhardt reports, the Duke University hospital system, which had 957 beds in 2017, employed 1,600 billing clerks.

[..] The prospect of actually being at risk for all your uninsured medical expenses was likely to concentrate their minds and remind them that, when it comes to health coverage, we all really are in the same pool.”

Column: A brilliant economist’s posthumous book diagnoses the US healthcare system – Los Angeles Times (2019.10.22)

“We refrain from proposing a specific life-gained threshold for selection of U.S. ever-smokers for screening, for several reasons. [..] the threshold would need to ensure that enough lung cancer deaths are prevented while maximizing the life-years gained in the population and maintaining screening efficiency. Balancing tradeoffs between prevention of death and extension of life and between screening efficiency and costs may be inherently a societal rather than a scientific question. [..] our estimations of life gained did not incorporate quality-of-life metrics.

[..] A shift to life-gained–based selection could have broad implications for precision cancer screening. Individualized life gained explicitly quantifies several implicit clinical considerations—disease risk, life expectancy, comorbidity and performance status, and the probability of benefits and harms of procedures and interventions—in a single metric. Life-gained–based selection could also unify the metrics for cancer screening across various stakeholders, including patients, clinicians, cost-effectiveness modelers, and guideline committees.

[..] In contrast to risk-based selection, life-gained–based selection circumvents the need for ages at initiation and cessation of screening because it naturally excludes persons with neither high enough disease risk to benefit from screening nor long enough life expectancy to gain life-years from screening, regardless of age. It also explicitly identifies persons with fewer comorbidities, better performance status, and favorable benefit–harm ratios. Thus, under such a framework, guidelines need only specify a minimum gain in life expectancy relative to harms to recommend persons for screening.

[..] A shift to life-gained–based selection would compound problems related to the time, effort, feasibility, and reliability of the collection of information on demographic characteristics; anthropometric measurements; risk behaviors; and multiple health conditions, many of which may not be readily available in health records. Likewise, ethical issues related to not offering or continuing screening for high-risk persons on the basis of life expectancy are common to all strategies, including age- and risk-based strategies, and would also need to be considered. Professional societies and guideline committees recommend discontinuing screening in older persons and those with short life expectancy. However, patients may be reluctant to hear about life expectancy or forgo screening on the basis of it. Recent research suggests that elderly persons are more likely to forgo screening when faced with shared decision making and positive messaging that conveys that the screening test is unlikely to help them live longer.”

From the accompanying editorial: “Future studies should also evaluate the acceptability of including race and socioeconomic status in calculations of lung cancer risk and life expectancy and the health equity implications of doing or not doing so.”

Life-Gained–Based Versus Risk-Based Selection of Smokers for Lung Cancer Screening (2019.10.22)

“Lots of information is available about drugs’ published list prices. But the drug distribution system is so complex — involving numerous middlemen and confidential negotiations for myriad rebates, fees and discounts — that manufacturers’ list prices are almost meaningless.

[..] In a new first-of-its-kind study of state drug pricing laws, my colleague and I found that 22 states had passed 35 bills that included some kind of transparency component between 2015 and 2018. But only seven of the bills went beyond requiring information that is already available.

Only two states required that net prices be reported: by insurers in Vermont and by manufacturers in Maine. Only Oregon and Nevada required that profits be reported by manufacturers.

Only Connecticut, Louisiana and Nevada required that pharmacy benefit managers — the big intermediaries that negotiate prices for insurers and employers — report rebates that they receive from drug makers. But even then, the requirement is only for aggregate reporting, not drug-by-drug.

Tracking how money flows in the aggregate is important, as a previous study shows. That will not substitute for drilling down into individual drug cases. For example, the reasons why insulin prices are rising may be very different than the dynamics affecting other generic drugs.

Importantly, no state passed laws that together revealed true transaction prices or profits across all supply chain segments.

To compound the problem, states have created a thicket of requirements that add to administrative costs without securing meaningful results. The laws vary widely, including the timing of disclosures (before or after a price increase), the type of information (price amounts, justification for increases, etc.) and what thresholds trigger disclosure. In many cases, the information submitted to the state is confidential, which inhibits media and academic oversight of the process.”

It’s hard to lower drug prices, if you don’t know what they are | TheHill (2019.10.19)

“If you offered sick people a choice between reforming the payment side of the system so that everything functions more like Medicare, or reforming the delivery side so that all hospitals function more like the Cleveland Clinic or Kaiser, they might well choose to reform the delivery side. Medical bills are scary, of course, but so is navigating through the fractured mazes of different systems that most very sick people end up caught between — in which vulnerable patients often feel like a lost package, or else an industrial input. So it’s worth asking why Democratic politicians — like too many health systems — seem so relentlessly focused on the money rather than the patients.

One answer is that reforming delivery systems is hard. The government can’t command other health systems to replicate the cultural values, or the institutional expertise, of a Kaiser Permanente or a Cleveland Clinic or a Mayo Clinic. All the government can do is alter payment schedules. And when the Obama administration tried to use that financial lever, it turned out that in the absence of a better institutional culture, patients saw, at best, marginal improvements. At worst, the results were perverse: New Medicare rules that penalized hospital readmissions seem to have resulted in the deaths of some patients.

Unfortunately, if Democrats aren’t going to reform the delivery system, then they probably can’t reform the payment system, either. Because unless America gets a handle on how patients are cared for, we can’t care for millions more of them at a price the American taxpayer will accept.”

Hey, Democrats, why not talk about health-care delivery, not just about costs? – The Washington Post (2019.10.18)

“One possible outcome is that the public option on offer could be robust and equitable, with good coverage, low premiums, and functionally solid mechanisms for automatic enrollment and the accurate determination of subsidies. (This is more likely under O’Rourke’s preferred Medicare for America proposal than Joe Biden’s plan, for example.) This would encourage many people to sign up, instead of sticking with their employer coverage. If this happens, private insurance could well get weaker; insurance company revenues would go down and additional costs would be passed on to patients in order to make up for the profit shortfall and maintain the plum salaries of executives. Fewer people being enrolled in private insurance might well mean insurance companies won’t have as much to offer to hospitals when negotiating prices (though they clearly already do a terrible job of that). Private insurance would die a drawn-out death, and it might not be pretty.

[..] The second possible outcome is that the public option could be mediocre or poor, with unreasonable premiums or poor coverage, which would not provide people much incentive to switch to it unless they had no other choice. (Hospitals and the private insurance industry would prefer this.) In this case, the public option will be relegated to second-class status, and those marooned there would experience all of the typical privations of downmarket health care coverage.

[..] Most lawmakers seem to agree that we shouldn’t use income to determine who has access to public schools, roads, or bridges. There’s nothing inherent to any of these areas of government activity that makes it obvious whether or not these programs should be universal or not; most of what determines that comes down to what a majority of decision-makers hold to be the role of government in society.”

The Public Option Bait and Switch | The New Republic (2019.10.17)