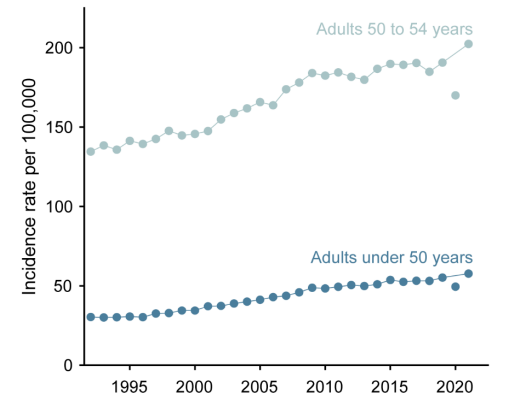

“early-onset cancer has emerged as a federal health priority. The Cancer Grand Challenges program, funded by the National Cancer Institute and Cancer Research UK, has allocated $25 million to uncover biological causes for rising rates. Early-onset cancer has also been highlighted as an area of scientific focus in the US National Cancer Plan. Research interest has concurrently surged, with the proportion of PubMed citations related to early-onset cancer more than tripling during the past 3 decades. Rising rates have also prompted recent shifts in policy, such as the US Preventive Services Task Force lowering the recommended initial age for colorectal cancer and breast cancer screening to 45 and 40 years, respectively. Despite these efforts, a critical question remains unanswered: are rising rates of early-onset cancer a true signal of increasing cancer occurrence?

[..] Although changes in incidence are important, they do not always have a straightforward interpretation. Rising incidence is typically interpreted as a rising occurrence of clinically meaningful cancer that must be attributed to hazardous exposures or behaviors. However, rising incidence can also reflect increased diagnostic scrutiny: the combined effect of more testing (eg, imaging and endoscopy), the improved ability of tests to detect small irregularities, and lowered diagnostic thresholds for labeling these as cancer. To better understand trends in incidence, it is crucial to evaluate another metric: mortality, specifically the annual rate of cancer deaths among adults younger than 50 years. While cause of death can be occasionally misclassified, mortality is much less affected by diagnostic scrutiny than incidence and is the most reliable measure of cancer burden. Thus, we examined population-based mortality trends for cancers with the fastest-rising early-onset incidence during the past 30 years in the US (which we defined as those with >1% increase per year on average): cancers of the thyroid, anus, kidney, small intestine, colorectum, endometrium, pancreas, and myeloma.

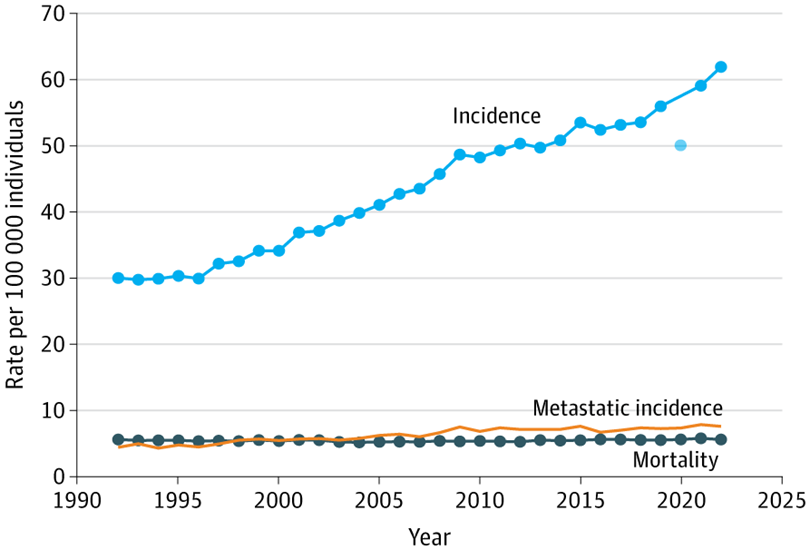

Since the 1990s, the aggregate early-onset incidence for these 8 cancers has approximately doubled, while their aggregate early-onset mortality has remained remarkably stable, with the rate in 2022 identical to that in 1992. In other words, these cancers are being diagnosed more frequently among young adults without a comparable shift in the feared outcome: death. The pattern suggests that, at least in aggregate, the increased incidence of early-onset cancers appears less an increase in the incidence of clinically meaningful cancer and more an increase in detection.

[..] Two cancers stand out because of increasing mortality: colorectal and endometrial. From its nadir in 2004, colorectal cancer mortality has increased approximately 0.5% per year, suggesting some increase in the occurrence of clinically meaningful cancer. However, its incidence has increased approximately 2% per year, raising the possibility that some of the rise in incidence may not involve clinically meaningful cancers. Instead, detection of neuroendocrine tumors, which account for a disproportionate share of the increased early-onset colorectal cancer cases, and the inclusion of appendiceal tumors (recently reclassified as malignant under updated cancer classification systems) may be contributing to an apparent increase in colorectal cancer incidence. For endometrial cancer, mortality and incidence have risen in parallel (approximately 2% per year), a trend likely explained by increasing rates of obesity and decreasing rates of hysterectomy (ie, a growing population at risk not captured by population-based rates: women with intact uteruses).

[..] Thyroid cancer diagnoses skyrocketed despite extremely stable mortality, a classic signature of overdiagnosis, ie the detection of disease that would never have caused death. Overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer is well documented. Kidney cancer diagnoses have increased rapidly despite falling mortality, likely reflecting incidental detection through increased use of abdominal imaging. Overdiagnosis of kidney cancer is also well documented. Anal cancer incidence has risen and subsequently declined, likely reflecting changing patterns of human papillomavirus infection and HIV. For the remaining gastrointestinal cancers (small intestine and pancreas), overdiagnosis likely explains the rising incidence and stable mortality, much of which reflects the incidental detection of small, indolent neuroendocrine tumors on cross-sectional imaging or endoscopy. Finally, the rising incidence of multiple myeloma without rising mortality may be explained by more widespread use of serum protein electrophoresis, with approximately a third of patients asymptomatic at presentation with incidental findings on routine laboratory panels.

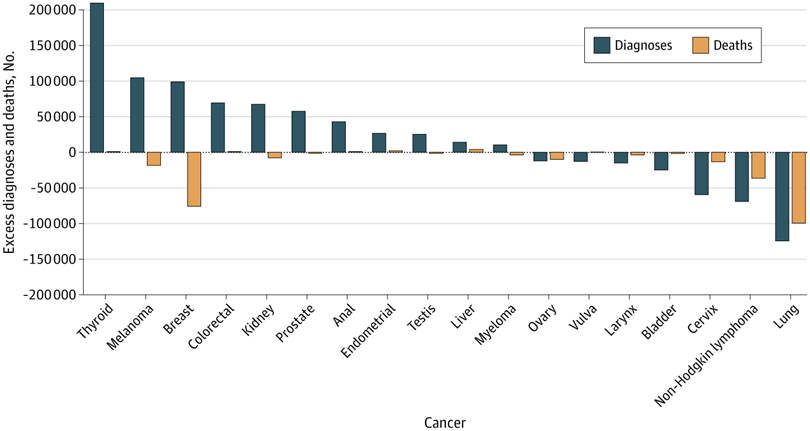

Given heightened attention in the media, some may be surprised that breast cancer is not among the cancers with the fastest increases in early-onset incidence. That is because the cancers highlighted earlier were selected based on their relative increase since 1992. While the relative increase in early-onset breast cancer has been modest (0.6% per year), the absolute number of excess cases among women younger than 50 years has been substantial, ranking third among all cancers (see figure below). This distinction matters: even small relative changes in common cancers can translate to many additional diagnoses. Although excess diagnoses have risen sharply, the number of excess deaths since 1992 is negative, reflecting the marked improvements in systemic therapy that have cut breast cancer mortality in women younger than 50 years by half during the past 30 years. Rising breast cancer incidence in women younger than 50 years largely reflects increases in early-stage cancers, with stable rates of regional and distant disease, a pattern that was observed in older women following the widespread adoption of screening mammography in the 1980s. Thus, the excess diagnoses similarly likely reflect the increased screening intensity in younger patients (ie, more mammograms, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging) than an increase in the occurrence of clinically meaningful breast cancer.

[..] Since 1992, more than 200 000 additional young women and men received diagnoses of thyroid cancer, while the number of deaths has remained virtually unchanged. Furthermore, there have been more than 100 000 additional diagnoses of melanoma and breast cancer, despite declines in deaths of each. At the other extreme, there have been roughly 130 000 fewer lung cancer diagnoses and nearly 100 000 fewer deaths, a remarkable public health success story that underscores the effect of the decline in cigarette smoking. There have also been substantial declines in non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnoses and deaths due to better HIV treatment, addressing a powerful risk factor, and improvements in lymphoma treatment itself.

[..] These patterns suggest that more cases are being found, not that more cases are occurring. This raises another possibility, that the rise may reflect earlier diagnosis rather than overdiagnosis. That is, some of these cancers (those that lead to death) are simply being detected sooner. A cancer once diagnosed at age 52 years might now be found at age 48 years due to more sensitive detection tools, creating the appearance of rising early-onset incidence without an actual increase in disease occurrence or a change in mortality. If this phenomenon were the primary explanation for the trend, we would expect diagnoses in older age groups to decrease proportionately with rising incidence in adults younger than 50 years, but no such compensatory decrease is apparent. Regardless of whether the pattern is mostly due to earlier diagnosis or overdiagnosis, the ultimate implication remains unchanged: for most of the cancers with rising early-onset incidence, more diagnoses do not necessarily mean an increase in clinically meaningful cancer.

[..] First, there is unambiguous good news in cancer: mortality of all cancers combined in adults younger than 50 years has decreased by nearly half since the 1990s. Second, other causes of death are equally relevant: deaths of cancer comprise only 10% of all deaths in adults younger than 50 years. Suicides and unintentional deaths (such as those from motor vehicle collisions or drug overdoses) outnumber cancer deaths more than 4-fold, and both are rising.

Unneeded cancer diagnoses (ie, those unlikely to result in symptoms or death) should concern everyone. A cancer diagnosis can profoundly disrupt the lives of young adults, turning those who may feel perfectly healthy into lifelong patients. The physical toll of cancer treatment is heightened in young adults and can include infertility, long-term organ damage, and secondary cancers. The emotional fallout is especially significant, as the long-term burden of anxiety and depression that comes with being labeled a cancer survivor can ripple through an individual’s family and community. Financially, the costs do not end with treatment; surveillance, follow-up care, and management of adverse effects often create long-term expenses. For young adults already dealing with limited savings and child care responsibilities, the financial strain can be devastating.

Policymakers, researchers, and the media must be cautious not to overinterpret rising incidence. Searching for biological causes for rising incidence in cancers without evidence of a rise in clinically meaningful cancer is bound to be unproductive. Chasing potential exposures is not just a waste of time, but also diverts funding, talent, and attention from addressing more important issues affecting young people in the US. It may alarm the public and perpetuate the idea that something in our environment or lifestyle is triggering more cancers, when physicians may simply be detecting more cases that were always present. Worse, it encourages the belief that young, healthy individuals could benefit from low-value screening interventions, such as whole-body imaging and multicancer early detection tests.

Our findings highlight the need for a more nuanced approach to early detection. More diagnoses do not necessarily mean more deaths, but they do mean more lives that will be profoundly changed. The challenge is to refine diagnosis to only detect and treat the cancers that truly matter. While some of the increase in early-onset cancer is likely real, it is small and confined to a few cancer sites. The epidemic narrative not only exaggerates the problem, but it may also exacerbate it. While more testing is often seen as the solution to an epidemic, it can just as easily be the cause.”

Full article, VR Patel, AS Adamson, and HG Welch, JAMA Internal Medicine, 2025.9.29