2020.9.29

“Annually, about 10 million people develop TB, and an estimated 1.5 million die from their disease, which makes it the leading infectious killer worldwide, even in the time of COVID-19.

[..] Key factors can significantly increase an individual’s risk. In particular, 2.3 million cases of TB were worldwide attributable to undernutrition in 2018: That’s one in five cases. By comparison, 1.2 million cases were attributable to HIV and 0.8 million cases to diabetes—risk factors that receive considerably more attention and funding. Undernutrition blunts the function of the immune system and increases the risk for TB so much so that it is likened to HIV/AIDS and called “nutritionally acquired immunodeficiency syndrome” or N-AIDS. Undernourished patients with TB get sicker, have more extensive lung damage, and are more likely to die from TB.

[..] Based on modeling studies, feeding an undernourished individual and increasing their body mass index (BMI) from 16 to 20 would decrease their risk for TB disease by about 50 percent. This would be as beneficial as the new TB vaccine, which is generating great enthusiasm. Of course, feeding people has benefits beyond mitigating TB risk: prevention of complications from vitamin and mineral deficiencies, protection against other infectious diseases, increased economic productivity, and decreased human suffering due to hunger.”

Meals As Medicine: Feed The Hungry To Treat The Tuberculosis Pandemic, Sinha P and Hochberg NS. Health Affairs Blog 2020.9.29

[Health Information Technology] “Technology-enabled eHealth programs represent potentially cost-efficient and practical means for customized PA [physical activity] guidance to diverse groups. Most people targeted by eHealth, however, are well educated, younger than 50 years, and of non-Hispanic White ancestry, potentially intensifying health disparities.

[..] This investigation tested whether a virtual advisor could increase 12-month walking to an extent similar to a comparably structured human advisor program among Latino adults. The human advisor program was delivered by trained peer advisors—a resource-efficient approach that is well accepted by Latino and other diverse groups but may be less convenient and scalable than computer-based programs. [..] Both interventions were considered “light-touch” given that they were delivered using primarily non–health professional staff and resources.

[..] COMPASS (Computerized Physical Activity Support for Seniors) was a single-blind, cluster-randomized noninferiority parallel trial10 conducted by Stanford University and Northeastern University. [..] They received a $10 gift card/assessment. Such modest remunerations have been found to have minimal influence on PA change.

Participants were recruited from community centers in Santa Clara and San Mateo counties, California. The centers were randomized in pairs (1:1 allocation) based on locale to either virtual or human advisors based on a computerized randomization sequence. [..] Both arms received a similar 12-month behavioral PA instruction/support program at their designated center based on Active Choices—an individually tailored program with demonstrated effectiveness and translatability that has merited formal recognition by the Administration on Aging, National Council on Aging, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[..] The following eligibility criteria were used13: (1) age 50 years or older; (2) insufficiently active (ie, engaged in <100 min/wk of moderate-intensity PA over the past month, based on the Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors [CHAMPS] instrument); (3) able to safely engage in moderate-intensity PA, such as walking, based on the PA Readiness Questionnaire; (4) live less than 5 miles from a study-designated community center; (5) be able to read and understand English or Spanish sufficiently to provide informed consent and participate in study procedures, including computer use; and (6) plan to live in the area for a year.

[After an introductory session,] Participants then received up to 28 brief (10-15 minutes) advising sessions across 12 months. Sessions followed a standard, evidence-based protocol and allowed for customization based on participant preferences and availability. Each session consisted of an introductory dialogue, brief check for health changes, review of pedometer steps and minutes walked since last session, problem-solving around personal PA barriers, goal-setting, and next-session scheduling. Cultural tailoring occurred in a variety of ways.

The virtual advisor, described elsewhere, was an interactive, animated computer agent simulating face-to-face counseling using simple speech (synthetic English or Spanish) and nonverbal behaviors (eg, facial cues and hand gestures). The virtual agent, named Carmen, was successful previously in increasing 4-month walking levels among Latino aging adults relative to controls. Individuals interacted with Carmen by touching simple conversation boxes on the computer screen offered in English and Spanish and targeted at a first- to third-grade reading level. Participants received a private log-in and were encouraged to wear headphones for privacy. They also were encouraged to download their pedometer data on the virtual computer at each session via a USB port. One difference between this system and some other automated health information systems is that participants could interact directly with this system at their convenience, receiving real-time customized advice through the multi-modality visual plus auditory interface.

[..] Change in walking minutes per week was assessed using the 4 walking items from the validated CHAMPS survey (interview format) for older adults, which is available in English and Spanish. Such standardized self-report instruments represent the most direct, reliable, and cost-efficient means for assessing specific PA types typically targeted in community interventions, given that device-based assessment tools (accelerometers) capture more general movement beyond such purposeful PA behavior and currently lack sufficient normative data, especially among older adults, to allow direct linkages with the PA guidelines and evidence base.

[..] A total of 241 participants (98.4%) were Latino, 193 participants were women (78.8%), and 52 participants were men (21.2%). Mean (SD) age was 62.3 (8.4) years (range, 50-87 years). One hundred seven participants (43.7%) had an education level of high school or lower. Mean (SD) years of residence in the US was 47.4 (17.0) years. Mean (SD) BMI was 32.8 (6.8), with 156 participants (63.7%) in the obese range. One hundred nineteen participants (48.6%) were taking antihypertensive medications. Reported walking time was low (mean [SD] total, 70 [98] min/wk; approximately 10-minute/d). Baseline accelerometry-derived MVPA [moderate to vigorous physical activity] per week also was low (mean [SD] virtual advisor, 40.7 [25.8]; human advisor, 43.6 [31.2]). One hundred six participants (43.3%) chose to receive their intervention in Spanish (virtual advisor, 48 [39.0%]; human advisor, 58 [47.5%]) (χ2 = 1.81, P = .18).

The mean (SD) number of total advising sessions completed for virtual vs human advisors was 18.8 (11.8) (64.8%) vs 18.4 (8.9) (63.4%) (t test, 0.30; P = .76). Mean length of postintroductory advising sessions was significantly shorter in virtual (8.4 [4.8] min/session) vs human (21.0 [7.1] min/session) (t test, 16.0, P < .001). This finding translates into a mean total intervention volume for virtual vs human of 3.2 hours (56.6) vs 6.9 hours (63.0) (t test, 27.8; P < .001). Although both programs encouraged pedometer use and reporting at each session, pedometer reporting was sporadic in both programs across 12 months (eg, month 12 reporting for virtual advisor, 35.8% vs human advisor, 32.8%; χ2 = 0.24; P = .62).

Twelve-month change in walking minutes per week [..] supported noninferiority (ie, lower limit of the 95% CI [−20.6] lay to the right of the noninferiority margin [−30]). Mean walking increases indicated a somewhat larger increase in the virtual advisor cohort (153.9 min/wk; 95% CI, 126.3 min/wk to infinity vs 131.9 min/wk; 95% CI, 101.4 min/wk to infinity; difference, 22.0, with lower limit of 1-sided 95% CI, −20.6 to infinity). Similar results were obtained using per-protocol analyses (mean [SD] increases in walking time for the virtual advisor cohort [n = 117]: 158.6 [217.1] min/wk vs human advisor cohort [n = 114]: 134.8 [192.1] min/wk; P = .02). At baseline, no participant was at the nationally recommended target range of 150 min/wk or more of MVPA; at 12 months, 29.3% of the virtual advisor and 31.1% of the human advisor cohorts achieved that target (χ2 = 0.10, P = .75).

[..] Both arms reported improvements in overall well-being, with the magnitude of the within-arm improvement somewhat larger in the human advisor (mean [SE] change, 3.5 [0.6]; t = 4.1; P < .001) compared with the virtual advisor (mean [SE] change, 1.1 [0.6]; t = 1.8; P = .06) cohorts. The human advisor cohort reported significant pre-post improvements in all 10 domains (eg, good appetite and few aches or pain), while the virtual advisor cohort reported significant improvements in 3 domains (sleep well, feel rested, and full of pep and energy).

[..] The results of the present trial expand the small PA eHealth evidence base for older adults and Latino populations across longer time frames. Both programs also produced reported decreases in prevalent sedentary behaviors, including television/video viewing, that have been linked independently with detrimental health outcomes.”

Effects of Counseling by Peer Human Advisors vs Computers to Increase Walking in Underserved Populations: The COMPASS Randomized Clinical Trial, King AC, Campero MI, Sheats JL et al. JAMA Internal Medicine 2020.9.28

[Clinical Pearl] “Intermittent fasting (IF) has gained attention as a simple weight loss method. Intermittent fasting refers to eating windows separated by defined periods of fasting (>12 hours and up to 48 hours, or more). Most of the reported benefits of IF are either untested or undertested in humans. Time-restricted eating (TRE) is a specific IF protocol involving consistent fasting and eating periods within a 24-hour cycle. [..] We conducted a randomized clinical trial (RCT) designed to determine the effect of TRE on weight and comprehensive metabolic outcomes in overweight and obese patients. We hypothesized that 8-hour TRE prescribed to individuals with overweight and obesity would lead to weight loss and improvements in metabolic markers compared with individuals following a standard 3-meals-per-day diet (consistent meal timing [CMT]).

[..] Participants received study surveys through the study app. Participants were given a bluetooth weight scale to use daily, which was connected through the study app. Participants were randomized to 1 of 2 interventions. The study intervention only included recommendations to the timing of food intake (no recommendation for calorie and macronutrient intake or physical activity), and participants received daily reminders about their eating windows through the app. The CMT group was instructed to eat 3 structured meals per day. Snacking between meals was permitted. The TRE group was instructed to eat ad libitum from 12:00 pm until 8:00 pm and completely abstain from caloric intake from 8:00 pm until 12:00 pm the following day (16 hours fast:8 hours eat). Only noncaloric beverages were permitted outside of the eating widow. Participants provided consent through the app, and received a $50 Visa gift card for participating in the study.

[..] Of the 141 participants who were randomized to 1 of the 2 interventions, 105 (74.5%) completed the entire 12-week intervention. [..] Self-reported adherence to the diets was 1002 of 1088 (92.1%) in the CMT group (did not miss any meals) and 1128 of 1351 (83.50%) in the TRE group (ate only within the 8-hour window).

[..] There was a significant decrease in weight in the TRE group (−0.94 kg; 95% CI, −1.68 kg to −0.20 kg) and a nonsignificant decrease in weight in the CMT group (−0.68 kg; 95% CI, −1.41 kg to 0.05 kg). Importantly, there was no significant difference in weight change between groups (−0.26 kg; 95% CI, −1.30 kg to 0.78 kg).

[..] As measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), there was no significant change in whole body fat mass (FM) in the TRE (−0.51 kg; 95% CI, −1.17 kg to 0.15 kg) or the CMT groups (−0.03 kg; 95% CI, −0.66 kg to 0.60 kg). [..] There was a significant decrease in lean mass (calculated as fat-free mass minus bone mineral content) in the TRE (−1.10 kg; 95% CI, −1.73 kg to −0.48 kg) but not in the CMT group (−0.35 kg; 95% CI, −0.95 kg to 0.25 kg). There was no significant difference in lean mass between groups (−0.75 kg; 99.7% CI, −1.96 kg to 0.45 kg).

[..] There were no significant within-group or between-group differences in fasting glucose, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, HbA1C, triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL, or HDL levels. [..] There was no significant difference in systolic blood pressure in the TRE group (−1.69 mm Hg; 95% CI, −5.54 mm Hg to 2.15 mm Hg), but there was a significant decrease in the CMT group (−3.86 mm Hg; 95% CI, −7.58 mm Hg to 0.14 mm Hg). There was no significant between-group difference in systolic blood pressure (2.17 mm Hg; 95% CI, −3.18 mm Hg to 7.52 mm Hg).

[..] Together, the results of this study (1) do not support the efficacy of TRE for weight loss, (2) highlight the importance of control interventions, and (3) offer caution about the potential effects of TRE on ALM. Future studies should be aimed at understanding the effects of early vs late TRE and protein intake or timing as a means to offset the loss in ALM [appendicular lean mass].”

Effects of Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss and Other Metabolic Parameters in Women and Men With Overweight and Obesity: The TREAT Randomized Clinical Trial, Lowe DA, Wu N, Rohdin-Bibby L et al. JAMA Internal Medicine 2020.9.28

[Health Technology] “Reporting of adverse events to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has long been the primary mechanism of identifying safety issues with medical devices—ranging from nasal swabs to cardiac defibrillators to in vitro diagnostic test kits. Each day, approximately 3500 adverse event reports are collected in the agency’s Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database. As anyone who has tried to use it will attest, the database provides a difficult-to-use interface to search these reports.

[..] The agency’s Sentinel System has successfully identified issues with drugs using a combination of claims and electronic health record data, but unlike MAUDE, the Sentinel System data are not publicly available, and the wait time for data requests can be several months. Drug-related adverse events are easier to link to Sentinel System data because of the National Drug Code, which uniquely identifies a drug so it can be linked directly to the report. In 2019, less than 2% of the 1.3 million adverse event reports for devices contained a Unique Device Identifier (UDI), and the UDI is often redacted by the FDA in whole or in part because the agency’s Freedom of Information Act team is unsure of which portions of the UDI are protected health information, even though only the serial number should be redacted. This redaction is important because all other methods of postmarket surveillance for medical devices in development by government agencies, hospitals, device registries, and insurance companies rely on the UDI. In addition, until all devices contain a UDI, the use of the Sentinel System for medical device surveillance is not feasible.

[..] The FDA should require immediately (and enforce) the listing of the UDI on every adverse event report and discontinue all redactions of the identifier to decrease chances that patients are not unknowingly receiving harmful devices.

The FDA could also improve medical device reporting by requiring that physicians submit reports directly to the FDA instead of the current system in which almost all these reports are first submitted to the manufacturer (often to get a replacement device or report an event). Under current law, only hospitals and manufacturers, not physicians, are mandated to report to the FDA. The Medical Device Guardians Act, a bipartisan bill introduced in the US House of Representatives in 2019, would provide the FDA with a mechanism to require that physicians report adverse events directly to the agency. Direct reporting with the UDI would greatly speed the time to identify signals and improve the chances that all the relevant details of the event are submitted. A copy of the report could be sent to the manufacturer simultaneously.

Data from the MAUDE database can be improved on, and even more can be done without waiting for the components of National Evaluation System for Health Technology to be implemented. For example, the FDA should reinstate the acceptance of adverse events via the Medwatcher, a third-party iPhone and Android application that allows submission of adverse events directly via smartphone and facilitates reporting by patients and physicians.”

Identification and Market Removal of Risky Medical Devices, Tomes M. JAMA Internal Medicine 2020.9.28

2020.9.28

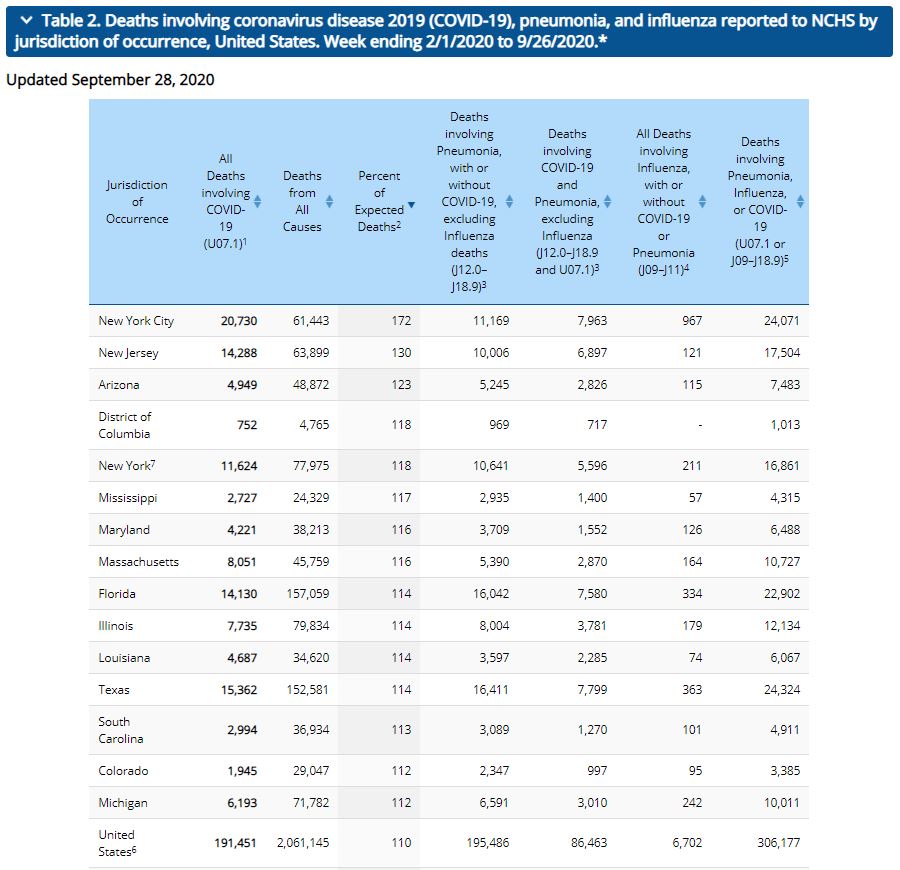

[COVID-19] The CDC updated its count of excess deaths by state earlier today. For the weeks between the week ending February 1st through the week ending September 26th, the national excess death rate was 110% (same as last week). Thirteen states, the District of Columbia and New York City are reporting excess death rates higher than the national average (same as last week). Georgia has an excess mortality rate of 110%. California, Georgia and Nevada all had an excess mortality rates of 110%.

New York City has the highest excess mortality rate (172% [down three percent]), followed by New Jersey (130% [down three percent]) and Arizona (123% [no change]).

[High-value Care] “Managing health care spending is critical considering that the U.S. health care economy exceeds $3.5 trillion. Between $760 billion and $935 billion is wasted on low-value care that costs considerably more than its clinical benefits are worth.

Giving Equal Weight to Valuation of Health Care Services and Technologies

[..] payer reimbursements for health care providers and biomedical manufacturers could not be more different. Medicare and other payers that adhere to Medicare payment structures use prospective payments based on diagnosis-related group for hospital services, and fee schedules based on relative value units for physician services. Payments have created a fundamental divide in Maryland and elsewhere, in that service costs are regulated but prices of biomedical interventions have increased in defense of supporting innovation. [..] A governing body that uses economic evaluation without discriminating between services and biomedical interventions stands to reduce wasteful spending across health systems.

Opportunity Costs

[..] Opportunity costs describe forgone benefits relating to the next best option when financial resources are committed to a particular activity. For example, spending resources on costly health care services, procedures, or pharmaceuticals can withdraw finances from other priorities, such as primary and preventive care.

[..] Overall, opportunity costs need to be considered in balance with health care benefits. Economic evaluation can identify decisions that maximize benefits and control costs—for example, establishing “cost-effectiveness thresholds” that represent the maximum a system can spend on health care before its benefits are outweighed by its opportunity costs.

Resource Prioritization With Value of Information [VOI]

[..] If applied effectively, VOI would move the United States ahead of other countries that use economic evaluation by enabling educated decisions about future research investments that lead to new innovations or more efficient resource allocation for patients who need targeted therapies. Research prioritization based on empirical methods would be a commonsensical way to allocate funding.

[..] VOI has not gained traction in the United States for several reasons. First, it does not always align with special interests that may aim to perform new trials in areas that offer little incremental value to the wealth of information. Second, it is linked to cost-effectiveness analysis, models, and thresholds, which have themselves been slow to become established. However, VOI can be used outside economic evaluation, as work funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute has shown.

The QALY

[..] The QALY expresses health status as a function of impacts on quality of life, including physical and mental components, and on survival and life expectancy. Limitations of QALYs are widely understood, including lack of sensitivity to some important changes in health and strong assumptions about inapplicable individual preferences. However, QALYs offer a well-understood, durable, and easily applied measure to inform resource allocation.

Addressing No-Value Care

[..] In the absence of an empirically evidenced threshold, there remain many low-value services and biomedical interventions that could be phased out. In particular, dominated interventions (“no-value care”) that increase costs but do not improve benefits are low-value options that do not need a threshold for decision makers to agree that they should be phased out. For example, a recent study identifying that individualized glycemic control for type 2 diabetes reduced costs and increased QALYs across several sociodemographic strata provided justification for phasing out outdated practices of uniform intensive glycemic control. In these situations, economic evaluation could reduce the availability of treatments that increase costs at reduced health benefit compared with more affordable alternatives, as well as protect these treatments for certain individuals who could still gain exceptional health benefit (such as minority populations).

State-Level Agreement on Value

[..] If the relative values of services and biomedical interventions are analyzed using economic evaluation, then opportunity costs, and hence cost-effectiveness thresholds, would vary greatly between states on the basis of high-cost health care decisions. For example, New York Medicaid’s formulary rejection of lumacaftor/ivacaftor (Orkambi [Vertex Pharmaceuticals]) for cystic fibrosis at the list price, in reference to ICER’s economic evaluation, implied that the product’s benefits were insufficient to justify the opportunity costs imposed on other patients at the acquisition price sought by the manufacturer. Alternatively, statewide policy in Louisiana to cover hepatitis C treatment for Medicaid beneficiaries may generate sufficient health benefits to justify opportunity costs imposed on others. However, for Mississippi, providing the same coverage for hepatitis C could come at such a high opportunity cost that it could not be justified on grounds of efficiency or equity. Therefore, the issue of redistribution of spending on health care and public health between states would follow.

[..] First, the United States could use economic evaluation only to phase out no-value care options. Second, it could establish a universal cost-effectiveness threshold at the level of the wealthiest or poorest state, with varying consequences: A threshold too high or too low could affect opportunity costs for some states. Third, cost-effectiveness thresholds could vary by state or clusters of states with similar levels of affordability (for example, quartiles). With the latter option, clusters could also organize value assessment commissions like Maryland did to make local decisions and spare separate states the duplication of effort. In addition, federal oversight of state processes could prevent situations where local-level decisions negatively affect persons in other places.

Finding a Collective Purpose for Economic Evaluation

[..] Health care in the United States is made up of fragmented payers, health systems, and innovators that do not have to play by similar rules. This is highly contrasted to other nations like England, where decisions by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence are linked to economic evaluation to recommend coverage decisions. The fact that the National Health Service and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence serve the same patients means that they have a collective purpose in England—to ensure that these patients have access to high-value care.

[..] The United States may be far off from adopting a single-payer system; however, short-term goals exist that could serve a collective purpose for economic evaluation. For instance, Medicare lacks a formulary to inform provider patterns of prescribing and ordering. If Medicare organized governance in value assessment to inform formulary-based decisions about coverage, then it would use taxpayer dollars to ensure that resources are allocated equitably among all beneficiaries.

[..] Likewise, if other payers and providers could begin to adopt the same rules of value through a central body like Medicare might do, then the collective purpose would spread while protecting the individuality of coverage plans and health systems. Some payers have indicated that they are already prepared to use economic evaluation in coverage decisions; for example, CVS Caremark announced that it would partner with ICER on economic evaluations assessed at a $100 000-per-QALY threshold. However, others lack transparency on how their benefit plans are structured. Meaningful use of economic evaluation among all stakeholders in health care delivery can happen only when the playing field is level and, as the previous point implies, when states offer important financial structure on which these institutions can model their economic evaluation.

Political Discourse for Economic Evaluation

[..] distributional cost-effectiveness analysis has been developed and applied to reflect the distribution of health outcomes across populations, and extended cost-effectiveness analysis has sought to incorporate concerns about financial risk protection to certain groups or individuals. Nonetheless, in order for economic evaluation to gain bipartisan support, liberals would have to compromise with conservatives on some other interests to introduce value assessment governance through federal legislation.

Perhaps for this reason, states may be best suited to address value locally. However, the single largest payer remains a federally funded one—Medicare—and the United States spends an average of more than $10 000 per capita on health care. Spending levels are astronomical, so there is no better time than now to introduce legislation that expresses a need for the United States to follow more economical practices in the allocation of health care resources. With U.S.-based organizations, such as ICER, prepared to handle some demand for economic evaluation, the United States could efficiently transition to more economical approaches for delivering health care.”

Ideas About Resourcing Health Care in the United States: Can Economic Evaluation Achieve Meaningful Use? Padula WV and Sculpher MJ. Annals of Internal Medicine 2020.9.29

[Drug Pricing] “The authors [Emanuel EJ et al. in a JAMA Internal Medicine Special Communication also published today] suggest that the United States should learn from its peers, from other developed nations that have created publicly accountable institutions for health technology assessment and drug price determination and that have reaped a return in the form of prices that are lower and better aligned with clinical value than drug prices in the United States.

[..] Payers in the United States (governmental programs, self-insured employers, insurers, pharmacy benefit managers) conduct their own implicit health technology assessments but usually without the transparency or evidence focus of the peer nations studied by Emanuel et al. [i.e., Australia, France, Germany, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom] [..] A review of coverage policies from the largest 17 private payers in the United States reported that only 15% of 4811 coverage policies had cited the same study evaluating a specific drug for a specific indication. US payers should be required to conduct their assessments in a transparent manner, with public proceedings and published findings, and give a clear evidence-based rationale for formulary exclusions and prior authorization requirements. Patient advocacy organizations and professional societies should have an opportunity to review and comment. Mandated transparency would push US payers toward standardizing their methods, as is occurring in Europe.

[..] There are 2 problems with the prevalent strategy for price negotiations in the United States. First, the interests of the payers are only imperfectly aligned with those of patients, employers, and taxpayers. Rebates are negotiated in strict confidence as are coverage and prior authorization decisions. Payers often favor high-price and high-rebate drugs over therapeutically similar low-price and low-rebate drugs because payers can retain a significant share of the rebates rather than pass them through to the patients, employers, and governmental programs.

Second, the method used by US payers to move from health technology assessment to price discounts imposes huge transaction costs on the system. Payers have numerous employees who create administrative restrictions on the ability of physicians to prescribe. These administrative access barriers are supplemented with onerous financial access barriers, including coinsurance and deductibles. In their turn, pharmaceutical firms have numerous employees who interact with physicians and who support patients, and thereby enhance sales revenues. Payers then further tighten administrative restrictions and increase cost sharing, leading the pharmaceutical industry to further increase its expenditures on marketing and patient support.

[..] One of the most admirable features of other developed nations, although not emphasized in the article by Emanuel and coauthors, is that these countries proceed from value assessment to price discount with much less bureaucratic involvement. The German system, for example, has a single national formulary that covers all drugs authorized by the European Medicines Agency, does not allow insurers to impose prior authorization on patients, and limits consumer cost sharing to a maximum of €10 per prescription (waived for children and patients with chronic illnesses).

The German system of drug assessment and price determination is of particular relevance to the United States because it relies on a system of multiple competing health insurance firms rather than the single public payer found in many other nations. German insurers must cover every innovative drug as soon as authorized by the European Medicines Agency and, in the first year after launch, pay the manufacturer’s full list price. During that first year, the semipublic Joint Federal Committee conducts a clinical assessment of the new drug in comparison to others that treat similar indications. This health technology assessment report is passed on to the association of insurers, which negotiates a price with the manufacturer based on the price of the comparator drug, the incremental benefit of the new drug, and the prices charged in other European nations (although in practice many novel drugs are launched first in Germany). All insurers then pay the same price for the new drug.7 Manufacturers are not permitted subsequently to increase the price of their drugs without submitting new evidence of clinical benefit and going through a new set of negotiations with the insurer association. The German approach has resulted in substantially lower drug prices than those paid in the United States both by private insurers and Medicare.

[..] Compared with the purchasing structures in the 6 countries described by Emanuel et al, purchasing pharmaceuticals in the United States is fragmented, unsophisticated, opaque, beset with conflicts of interest, and not surprisingly, ineffective. Prices are higher in the United States than in other nations of comparable income. There is no consistent alignment between drug prices and clinical value. Insurance coverage policies are not based on scientific evidence in a consistent and transparent manner. Physicians’ prescriptions are frequently rejected based on financial grounds. High cost sharing burdens many patients with severe illness and adds to already serious failures of prescription adherence.

It does not have to be like this. Other nations are more efficient in their purchasing processes, more effective in their outcomes, and more ethical in how they treat patients with respect to drug pricing. The United States has much to learn.”

Sophisticated Purchasing of Pharmaceuticals: Learning From Other Countries, Robinson JC. JAMA 2020.9.28

[Interesting] “[physician and health reporter James] Hamblin’s new book, Clean: The New Science of Skin, is a documentary survey of this pre-dawn moment in our understanding of the skin microbiome.

[Emily Vaughn] Your book sets out to challenge some cultural norms about hygiene. What types of cleansing do you think are overdue for reexamination, and which are critical?

[James Hamblin] There’s a distinction between “hygiene” and “cleansing rituals” that’s especially important in this moment. “Hygiene” is the more scientific or public health term, where you’re really talking about disease avoidance or disease prevention behaviors. Removal of mucus, vomit, blood feces … any behavior that signals to people “I am thoughtful about not transmitting diseases to you, and I’m a safe person to be around.” That would include hand-washing, brushing your teeth, cleaning of open wounds, even mask-wearing. I don’t think any of that stuff is due for questioning.

But a lot of the other things that we do are class and wealth signifiers — like combing your hair or whitening your teeth or wearing deodorant — which actually have nothing to do with disease avoidance or disease transmission. They’re really much more of a personal or cultural preference. And that’s where people are experimenting with doing less.

[Emily Vaughn] Why do you think that some of these cultural practices deserve to be reexamined?

[James Hamblin] So many reasons. We’re spending a lot of money (or at least we were pre-pandemic, I don’t have new data) on products and practices in this enormous industry-complex of self-care, skin care, hygiene and cosmetics — which is barely regulated, which is a huge and important part of people’s daily lives, which people worry a lot about, which people get a lot of joy from, which people bond over, which people judge, and which causes a lot environmental impacts in terms of water and plastic.

And there’s the emerging science of the skin microbiome. Being clean [has historically] meant removing microbes from ourselves, so it’s an important moment to try to clarify what, exactly, we’re trying to do when we’re doing the hygiene behaviors. [..]

[Emily Vaughn] You wrote that you think we’re at the edge of a radical reconception of what it means to be clean. What do you mean by that?

[James Hamblin] That’s harder to answer now because I don’t know how the current moment is going to change things. But I believe there’s a shift in the very near future upon us, similar to what we saw with the gut microbiome.

Twenty years ago, the idea of kombucha, and probiotics, and trying to have a healthy biome in your gut were really fringe hippie concepts. And now we’re doing clinical trials of fecal transplants. It’s very mainstream to think about your microbiome. People are being more conscious about things like antibiotic overuse because they don’t want to potentially disrupt the gut microbiome. That has been a really radical shift.

And something like that [for] the skin would be even more radical in terms of the effect on our daily lives, and consumer behaviors and spending, because a lot of what has been done traditionally [in terms of hygiene] is predicated on eradicating microbes. [..]

[Emily Vaughn] What’s the danger of that fine line [between drugs and beauty products here, which makes it very hard for consumers to know]?

[James Hamblin] Most likely these products are not doing anything. Because there’s so little regulatory oversight on this type of product, we don’t even know for sure that they contain what they claim to contain. And if they were significantly changing your skin microbes, I would want to be extremely careful that there was indeed evidence to back up that that change was good and worth making.

I think a lot of people buy products like this thinking, “It can’t hurt, right?” And I would suggest keeping in mind that if something can help, that it can hurt.”

In The Era Of Hygiene, ‘Clean’ Author Makes The Case For Showering Less, Vaughn E. Shots: Health News from NPR 2020.9.26

[Inequality] “Just as the Black Lives Matter movement has highlighted racial inequities in law enforcement, so the lopsided toll of Black victims in the pandemic has revealed them in health care. Hospital policing is where these two disparities collide. Cleveland’s prestigious hospitals, which mainly employ and treat whites, are surrounded by low-income Black neighborhoods with some of the worst health outcomes in Ohio, including lower life expectancy and high rates of asthma, diabetes and infant mortality.

Hospitals have replaced the factories and plants of a faded industrial era as the most important economic engine in northeast Ohio. The clinic [Cleveland Clinic] surpassed Walmart last year to become Ohio’s largest employer, with more than 50,000 employees. It is consistently ranked as one of the top three hospital systems in the country in both quality of care and size.

[..] Revenues for the clinic system [Cleveland Clinic], which also includes hospitals in two other states and three countries, were just over $10 billion in 2019. The presidential debate will take place in the Samson Pavilion, which features a massive steel roof and soaring 80-foot-high indoor courtyard. It’s the centerpiece of a half-billion-dollar health education campus that opened last year.

In many other cities, University Hospitals would be the biggest health care system. As it is, the UH system is the second-largest employer in northeast Ohio. Its 2018 revenues topped $4 billion. The hospitals are separated on Euclid by the campus of Case Western Reserve University, which has its own police force.

[..] Cleveland’s hospital zone may be one of the most heavily policed areas in the country. Besides the private police agencies, the city police patrol the area, as does the Greater Cleveland Regional Authority Transit Police Department. City police handle most of the major crimes in the area. Calls for help made from the hospital area through the 911 system still go to city police, although there are times when the city department will contact the private agencies for help. Still, the hospital police forces initiate most of their own arrests and citations, often prompted by a traffic stop, a call from hospital staff or someone acting suspicious.”

What Trump and Biden Should Debate at the Cleveland Clinic: Why the Hospital’s Private Police Mostly Arrest Black People, Armstrong D. ProPublica 2020.9.28

[Policy] “Trump’s plan is to ship seniors $200 prescription drug coupons in the coming weeks, a massive, $6.6 billion initiative that he announced less than six weeks before Election Day. He is relying on the same authority that Obama used in 2010 to bolster a more expensive, albeit less outwardly political, plan to direct bonus payments to high-performing insurance companies ahead of his own reelection campaign.

[..] Both the Obama and Trump controversies surround so-called demonstration authority, a power granted to the White House to test whether changes to Medicare to make the program run smoother or save money.

Obama used that authority to change the bonuses for high-performing insurers that contract with Medicare. The plan, which was meant to test whether “stronger financial incentives and investments” would lead plans to offer better quality insurance coverage, would have doled out lucrative bonuses to 90% of private insurers.

Republicans saw it as an attempt to insulate seniors from spiking insurance premiums before an election. They argued that the Obama administration was robbing money from a different health program to prop up the Affordable Care Act and doling out the bonuses to make sure seniors didn’t feel the brunt of the cuts before the election.

“An honest way to come to the Congress is: Look, we screwed up, we would destroy Medicare Advantage if we didn’t bail it out, so we came up with a scheme to bail it out, that’s what you did,” said Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.), who led the Republican investigation into the project.

[..] Both the GAO [Government Accountability Office] and lawmakers noted that the absence of a control group made it difficult to conduct an experiment to measure the program’s effectiveness. The GAO ultimately found that the Obama administration likely exceeded its authority and recommended the demonstration be canceled.

“There was clearly oversight following that demonstration,” said Jon Blum, the former Obama administration official hauled before Congress after the Obama demonstration. Blum added that he believed many of the criticisms waged at the Obama demonstration, like the lack of a control group, likely could plague the Trump ploy, too.

Trump’s plan is more brazen. It’s not clear how the Trump administration might test whether the payments had their intended goal if all seniors in Medicare are getting payments — or what the administration is planning to test at all.”

Republicans blasted Obama’s use of an obscure Medicare law. Now Trump’s using it on $200 drug coupons — and the GOP is silent, Florko N and Facher L. Stat News 2020.9.25

2020.9.27

[COVID-19] Excerpt – Unless you are living with an infected person — in which case the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers specific guidelines to follow — protecting yourself at home does not require extraordinary measures, Dr. [Virginia Tech’s Linsey] Marr said. And when you venture elsewhere, wearing a face covering and washing your hands are still the best ways to protect yourself indoors.

Health experts offered several tips for dodging the virus indoors: Open the windows, buy an air filter — and forget the ultraviolet lights. Fear of the risk of transmission indoors has fueled a market for expensive devices that promise to scrub surfaces — and even the air — but most of those products are overkill and may even have unintended harmful consequences.

“Anything that sounds fancy and isn’t tried-and-true — those are all things to avoid,” said Delphine Farmer, an atmospheric chemist at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. “Soap and water work beautifully.”

Managers of larger buildings should encourage those who can to work from home and adopt strategies like adding air filters and disinfecting surfaces. Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have created an app to determine how many people can safely congregate in a given space and for how long.

But regardless of these precautions, the optimal strategy is simply to wear a mask indoors, said Martin Bazant, a chemical engineer at M.I.T., adding, “That’s a much bigger effect than any of those strategies would provide.”

[..] Unlike portable air filters that are inexpensive and can simply be plugged into an electrical outlet, UV lights need to be carefully engineered by trained individuals in order to disinfect. Installed incorrectly, they can cause skin burns and damage eyesight, said Saskia Popescu, a hospital epidemiologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

UV lights are regulated mostly for use as pesticides and are not well studied for use around people, she added: “I get really nervous when I see people pushing UV disinfection.”

UV light generally does not penetrate deep into a surface and will not destroy virus that’s buried beneath other microscopic detritus.

[..] “Everybody is inundated right now with the shiny new solutions that are being sold to them,” Dr. [building safety expert at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health Joseph] Allen said. “And the reality is, it’s a time for the basics.”

How to Keep the Coronavirus at Bay Indoors, Mandavilli A. New York Times, 2020.9.27

[Health Information Technology]”This systematic review identified and summarized EHR-integrated systems to remotely collect patient-reported symptoms and examined their anticipated and realized benefits in long-term conditions.

[Results] We included 12 studies representing 10 systems. Seven were in oncology. Systems were technically and functionally heterogeneous, with the majority being fully integrated (data viewable in the EHR). Half of the systems enabled regular symptom tracking between visits. We identified 3 symptom report-guided clinical workflows: Consultation-only (data used during consultation, n = 5), alert-based (real-time alerts for providers, n = 4) and patient-initiated visits (n = 1). Few author-described anticipated benefits, primarily to improve communication and resultant health outcomes, were realized based on the study results, and were only supported by evidence from early-stage qualitative studies. Studies were primarily feasibility and pilot studies of acceptable quality.

[Discussion/Conclusions] EHR-integrated remote symptom monitoring is possible, but there are few published efforts to inform development of these systems. Currently there is limited evidence that this improves care and outcomes, warranting future robust, quantitative studies of efficacy and effectiveness.”

Remote symptom monitoring integrated into electronic health records: A systematic review, Gandrup J Ali SM, McBeth J et al. JAMIA 2020.9.23

[Epidemiology] “Described as the “greatest global challenge for health and social care in the 21st century,” dementia is a debilitating disease that affects about 50 million individuals worldwide, a number projected to triple by 2050. Given the limited efficacy of current dementia treatments, society stands to benefit tremendously from public health prevention strategies. Hearing loss (HL) has been recently shown to be a treatable risk factor for dementia.

[..] Clinicians may be tempted to use the known independent association between HL and cognition to justify HL treatment (eg, hearing aids) to prevent age-related cognitive deficits. While appropriate management of HL is certainly recommended, a clear causal linkage between HL and cognition has yet to be found. In the meantime, the low risk and growing theoretical benefit of HL treatment warrant improved efforts to broadly test and treat. This article [a manuscript identifying an association between poorer hearing with longitudinal change in white matter microstructure] supports ongoing public health and legislative efforts to improve hearing health care.

Randomized clinical trials are the criterion standard for studying causal relationships; however, they may be impractical or even unethical to perform. For example, ensuring continuous wear of hearing aids throughout a clinical trial may be difficult because adherence is low, and prolonged withholding of hearing aids from an individual with HL may be unethical. Nonetheless, future prospective studies should be performed to further elucidate longitudinal relationships between HL and WM [brain white matter] microstructure. In particular, replication of these findings by other investigators using more diverse populations and various DTI [diffusion tensor imaging] approaches over a longer follow-up will be necessary to substantiate these findings.”

Mapping the Brain Effects of Hearing Loss: The Matter of White Matter, Chern A, Irace AL, and Golub JS. JAMA Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery 2020.9.3

[Care Delivery Innovation] “Franklin Pharmacy is part of a UnitedHealthcare experiment in Ohio to put community pharmacists on the team of clinicians who care for a patient in hope of controlling chronic conditions and reducing hospital readmissions. The insurer is paying pharmacists to have these conversations, uncover any health and medication issues, and then do something about them.

“We tend to have better results in getting people care when we’re working with them within their communities,” said Michael Roaldi, who leads UnitedHealthcare’s Medicaid business in the state. “It occurred to us that pharmacies—community pharmacies and chain pharmacies—are literally thousands of examples of medical professionals in people’s communities that they regularly interact with that can be a conduit for receiving care.”

A number of other insurers in the state, including Centene-owned Buckeye Health Plan, CareSource, and Molina Healthcare, are rolling out similar pilots focused on Medicaid members in anticipation of new rules from the Ohio Department of Medicaid that would formally recognize pharmacists as healthcare providers and reimburse them for services that go beyond counting pills.

[..] “We’re at the beginning of a care revolution here,” said Antonio Ciaccia, former director of government and public affairs at the Ohio Pharmacists Association who was recently named a senior adviser to the American Pharmacists Association. “Once the diagnosis is made and the patient is on established therapy, having the pharmacist act as a touchpoint to make sure the patient is adequately calibrated on the therapy plan and on progress to meet their goal—that is right in their wheelhouse.”

[..] While there are a few mechanisms through which pharmacists can be paid for services beyond dispensing drugs and administering vaccinations, payment opportunities are limited, and that’s especially true for community pharmacists, said Anne Burns, vice president of professional affairs at the American Pharmacists Association.

A major reason is that Medicare Part B does not recognize pharmacists as healthcare providers, so pharmacists can’t bill the program for their services. Because other payers look to Medicare for guidance, CMS’ refusal to recognize pharmacists has dampened uptake of their services elsewhere, Burns said.

[..] Pharmacists have long argued their extensive training, medication expertise and accessibility could be tapped to manage patients with chronic diseases, who drive the bulk of healthcare spending. Their inclusion on the care team could alleviate the effects of the physician shortage on patients, they say. According to the National Association of Chain Drug Stores, 9 in 10 Americans live within 5 miles of a pharmacy.

[..] A wealth of evidence shows pharmacists have helped improve clinical outcomes for people with diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and other chronic illnesses. Some studies have also found that pharmacist interventions save healthcare costs. One review estimated that every $1 invested in clinical pharmacy services produced savings and other economic benefits of nearly $5.

Meanwhile, payment for dispensing has become tighter and tighter. Pharmacists are forced to fill prescriptions faster to stay afloat, leaving little time or incentive to counsel patients.

[..] pharmacy transformation is underway in Ohio. A law that took effect in April 2019 not only recognized pharmacists as healthcare providers but gave insurers the option to pay for higher-level pharmacist-provided services under the medical benefit. Pharmacists are usually reimbursed not by the insurer, but by the pharmacy benefit manager through the separate drug benefit, where incentives and goals differ.

Several other states, including Tennessee and Washington, have passed stricter laws that fostered payment for pharmacist services. [The other four states identified by the National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations were New Mexico, Texas, West Virginia and Virginia.]

Many pharmacists, particularly those working in clinics, are now billing insurers as healthcare providers in Washington. Getting community pharmacists set up to bill health plans has been a heavier lift, said Jeff Rochon, CEO of the Washington State Pharmacy Association. Tennessee has also made strides, but both states have been more successful at getting local commercial plans on board. National insurers like UnitedHealthcare have been slower to adjust, Rochon said.

[..] “Don’t you want to incentivize the pharmacist to actually get them on the right medicine, make sure the dosing is correct and monitor those medications to see if the patient’s getting better? That’s the incentive I’m going for, and those are the same incentives and the same metrics these payers and primary-care offices are currently being held to, and they’re not meeting them,” said Stuart Beatty, associate professor of clinical pharmacy at Ohio State University who directs strategy and practice transformation at the pharmacists association.

[..] One by one, Ohio health insurers began to bite. Most of the five Medicaid managed-care companies in the state have rolled out their own programs to experiment with how they can best use pharmacists’ expertise to care for Medicaid patients, each taking a different approach to ensure care doesn’t become duplicative or fragmented.

[..] UnitedHealthcare’s program gave pharmacists flexibility in who they see and what they can do within their scope of practice. It encourages pharmacists to keep the primary-care physician in the loop by paying them for time spent coordinating care with the doctor.

A six-month pilot launched in August by CareSource, the largest Medicaid managed-care insurer in the state, is more prescriptive and requires pharmacists to enter upfront agreements with primary-care doctors who will sign off on which basic services they are comfortable delegating to pharmacists. A physician may allow the pharmacist to adjust or prescribe new medications, for instance.

[..] For now, insurers are paying pharmacists for extra services out of their own pockets. CareSource said it’s paying pharmacists $25 for 15 minutes spent with the patient, and will move to medical code billing as soon it can. UnitedHealth said it is paying pharmacists based off the physician fee schedule but at a reduced rate.

Under draft rules, the Ohio Department of Medicaid would foot the bill for high-level services provided to the state’s 3 million Medicaid enrollees. Most members receive benefits through private insurers that contract with the state to manage their care.

[..] [Ohio Medicaid director Maureen] Corcoran said pharmacists would be able to bill evaluation and management codes for clinical consultations on asthma, diabetes, cancer or any condition that involves medication. The draft rules, which could change during the rulemaking process, specify payment for managing medication therapy and administering immunizations and certain medications.

Like in CareSource’s program, the department would require a pharmacist to have an agreement with a patient’s primary-care doctor, rather than acting independently. Some groups, including the National Community Pharmacists Association, have said the draft rules are too narrow and would unnecessarily limit what a pharmacist can do.

Insurers will adapt their programs to meet the Medicaid department’s rules when finalized early next year. They could still choose to pay for pharmacist services beyond what the state pays for, but the companies would be footing the bill. Each pharmacist who wants to bill Medicaid for these higher-level services would have to enroll in the safety net program.

[..] The billing process has been especially difficult to nail down because it hasn’t been defined, she [Meera Patel-Zook, vice president of pharmacy operations at Buckeye Health Plan] said. Buckeye’s pilot that launched in June started with two federally qualified health centers and a hospital system because they already had pharmacists embedded in their facilities and were used to collaborating. The pilot will soon include two independent community pharmacies, and the variety of settings helps the insurer test how processes will differ between them.

[..] Other challenges include getting patients and physicians to embrace the changes. Todd Baker, CEO of the Ohio State Medical Association, said the group opposes giving pharmacists independent authority to prescribe medications and order or interpret tests.”

I work for UnitedHealthcare.

Pharmacists in Ohio managing care as providers—and getting paid for it too, Livingston S. Modern Healthcare, 2020.9.26

[..] The new data show that outbreaks linked to parties, bars, dormitories and other crowded venues are hazardous not just to the 20-somethings who are present, but to more vulnerable Americans with whom they are likely to come into contact.

[..] “This is what we worried would happen if young adults started regathering in higher numbers,” said Dr. Tom Inglesby, director of the Center for Health Security at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

[..] He said the patterns are “yet more evidence that the concept proposed by some — cocoon the elderly, and let young people get sick because they will not have bad outcomes — will not work.”

Virus Cases Surged in Young Adults. The Elderly Were Hit Next. Rabin RC. New York Times, 2020.9.24

2020.9.25

“There are multiple examples of existing independent federal agencies, including the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Trade Commission, that can make decisions swiftly during national crises without Presidential or Congressional approval. A framework of essential attributes shared across these agencies has previously been described in a proposal to make the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) independent, including the following key attributes:

- a single director appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate (akin to that of the Federal Reserve),

- rule-making authority in accordance with Congressional enabling legislation and intent,

- oversight by the Office of Management and Budget limited to significant regulations and policy development, and

- independent litigation authority through the Department of Justice.

As an independent federal agency, the CDC could be governed by a single director and include a governing board with diverse lifetime experiences in public health. Additionally, to prevent politicization of the board, each member could require Senate confirmation to be appointed, serve staggered terms that span multiple presidential and congressional terms, and receive protections from budgetary cuts. Many independent agencies are not subject to regular congressional appropriation and authorization processes for funding. Some agencies, including the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, determine their own budgets, with some limitations enforced by Congress, and are not required to submit their request for review by the Office of Management and Budget. A similar degree of autonomy for the CDC could help ensure it maintains funding required to protect public health regardless of the political climate.

To ensure accountability, CDC board members could be removed for cause and reappointed via congressional approval. The CDC could also have some rule-making (eg, nationwide mandates, emergency declarations) supervised by the Office of Management and Budget. Importantly, to counterbalance federal oversight, the CDC could have independent litigation authority through the Department of Justice to challenge excessive oversight. This balancing of authority would safeguard against politicization from those acting in bad faith who belong to either entity.

[..] Given the saga of the nation’s response to COVID-19, the CDC needs to be freed from its politicized governance. Without the capacity to act autonomously, the CDC will continue to be constrained by politics—undermining the public’s trust in the agency and risking the nation’s health.”

The Case for Independent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—Protecting Public Health from Politics Shah S and Forman H. JAMA Health Forum 2020.9.25

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality plans to release a survey next month that providers can use to assess patient experience with telehealth visits. [..] AHRQ, which oversees and funds a suite of widely used patient experience surveys called Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS), will release the survey sometime in October as a beta version to any providers who want to use it, according to Caren Ginsberg, director of the CAHPS program at AHRQ [..].

The survey won’t have the CAHPS logo because it hasn’t gone through the long approval process including field testing, but Ginsberg said AHRQ leaders thought it was important providers had access to the survey soon given the expanded use of telehealth.

[..] Most reports show patients are satisfied with telehealth although there are concerns the platform isn’t improving access for everyone, particularly those who don’t have reliable access to broadband or devices.

[..] Right now, Medicare requires hospitals to participate in the Hospital CAHPS survey, known as HCAHPS, but it must be administered through mail or phone, which hospital leaders say is outdated and unhelpful to them. Responding to those complaints, CMS plans to test in the spring a “web mode” version of multiple patient experience surveys and for HCAHPS, it will ask a nationally representative group of hospitals to participate, according to an agency spokeswoman. The testing is scheduled to begin in April 2021, but the spokeswoman said COVID-19 may cause delays.”

AHRQ plans to release a telehealth patient experience survey Castellucci M. Modern Healthcare 2020.9.24

2020.9.24

The Trump administration and House Democrats share one idea regarding pharmaceutical price controls: They agree that the US should use an international price index that averages prices paid by other countries (mostly European) to cap the US prices. PhRMA has long opposed such policies, recently renewing its opposition. Unacknowledged and perhaps unknown to those proposing this reform is that at least 25 EU nations employ a pharmaceutical price index to cap their own drug prices.

In July 2020, President Donald Trump signed an executive order indicating he would soon implement an earlier international price index (IPI) proposal that would cap drug prices in Medicare Part B (for drugs used in hospitals). [..] In contrast, the House Democrats bill would cap drug prices for all of Medicare and private insurers based on an Average International Market (AIM) Index, which is the volume-weighted average of each drug price in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

[Key Lessons from European Nations]

- The IPI should be based on maximum reimbursement after discounts or on net prices—not on official prices.

- Employ health technology assessment (HTA) to determine the therapeutic value of new drugs to cap reimbursement, in addition to employing a cap based on an IPI.

- Employ index prices to cap prices for drugs that are superior to existing products, but cap prices of other drugs based on the price of comparable products.

- Use competitive bidding to obtain drugs at lower prices than maximum reimbursement allowed.

The official maximum reimbursement prices are significantly more—by some estimates between 10 percent and 30 percent more—than that maximum amount allowed after confidential discounts are subtracted. In addition, the procurement price is often subsequently reduced by clawback payments: For example, in France, Parliament sets an annual maximum spending growth rate. If the spending exceeds the budget, firms pay 50 percent to 70 percent of their sales revenue after the budget cap is surpassed, depending on the amount of overspending.

[..] A US international drug price index used to cap prices should estimate actual amounts reimbursed, or net prices, not official prices prior to discounts. Nor need the US pay 120 percent of what comparably wealthy countries are paying. With a larger market, the US has greater bargaining power than individual European nations and can use this to negotiate price discounts. Nor need the US allow pharmaceutical firms to raise prices subsequently to account for inflation, since European nations that employ an IPI do not allow price increases for inflation.

Although the US has used competitive bidding to procure certain federal supplies, it has not generally employed this strategy to procure drugs for Medicare and Medicaid.”

Average International Market Pricing For US Pharmaceuticals—Lessons From Europe Rodwin MA. Health Affairs Blog 2020.9.24

“One decade after passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), despite substantial gains in insurance coverage, health care affordability remains a major concern among US residents. Premiums are increasingly unaffordable, and underinsurance—incomplete financial protection despite coverage—is increasingly common. Although previous research has shown that the ACA’s Medicaid expansions decreased out-of-pocket spending among low-income adults, broader trends in out-of-pocket spending have not been well characterized.

[..] We obtained income, insurance coverage, and spending data from a nationally representative sample of adults aged 20 to 64 years in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, collected from 2010 to 2017. Our primary outcome was catastrophic health expenditures, defined with the World Health Organization threshold of calendar-year out-of-pocket plus premium spending exceeding 40% of postsubsistence income (calendar-year income minus typical food and housing expenditures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics).

We identified 159 941 survey respondents (49.1% men; mean age, 41.8 years [SD, 12.6 years]), representing 186 million individuals annually after survey weighting. The number of uninsured nonelderly adults declined from 42.9 million (23.5%) in 2010 to 27.9 million (14.8%) in 2017, whereas those with Medicaid coverage increased from 11.0 million (6.0%) to 18.3 million (9.7%) (P < .001). Coverage gains were concentrated in the 2 lower income quartiles, in which the uninsured rate decreased from 44.1% to 28.6% (lowest quartile) and 27.0% to 18.7% (P < .001).

The number of adults experiencing catastrophic expenditures yearly declined from 13.6 million (7.4%) in 2010 to 11.2 million (5.9%) in 2017 (P < .001). Privately insured adults composed 46.4% of catastrophic expenditure cases in 2010 and 53.6% in 2017 (P < .001).

In our interrupted time series analysis, individuals in the lowest income quartile experienced a 2.3 percentage point decrease in likelihood of catastrophic expenditures (95% CI, −4.6 to −0.1), whereas no change was observed in other income quartiles. Stratified by insurance type, privately insured individuals experienced no change in catastrophic expenditures (adjusted change, −0.2 percentage point; 95% CI, −1.4 to 1.0). Finally, in our subanalysis of the lowest income quartile, privately insured individuals again experienced no change (adjusted change, −2.8 percentage points; 95% CI, −9.5 to 3.8), and in fact had the highest rate of catastrophic spending in 2017 (34.6% vs 8.3% among Medicaid enrollees and 13.9% among the uninsured).

ACA implementation was associated with 2 million fewer US adults with catastrophic expenditures each year. Financial protection improved for the lowest income quartile, which was one of the ACA’s principal aims. However, improvements were not observed in higher income quartiles or among the privately insured, who represent an increasing share of those experiencing catastrophic expenditures. Among individuals in the poorest quartile, the privately insured are the most vulnerable, with one-third experiencing catastrophic spending annually.

Despite large coverage gains, 11 million US adults, including 6 million with private insurance, continue to experience catastrophic health expenditures annually. [..] Health reform should move beyond expanding insurance coverage alone to address persistently high out-of-pocket spending among the insured.”

Catastrophic Health Expenditures Across Insurance Types and Incomes Before and After the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Liu C, Chhabra KR and Scott JW. NAMA Network Open 2020.9.24

“Whereas brachytherapy (BT) and dose-escalated external beam radiotherapy (DE-EBRT) have longstanding use in the treatment of patients with localized prostate cancer (CaP), stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is an emerging option owing to cost effectiveness, patient convenience, and noninferior tumor control and acute toxic effects. The increase in radiation options and paucity of comparative evidence present challenges in guiding patient-centered care. Using the National Cancer Database, we compared use and outcomes between SBRT, BT, and EBRT for the treatment of patients with intermediate risk CaP.

[..] patients were identified in the National Cancer Database who had National Comprehensive Cancer Network intermediate risk CaP (Gleason score of 6-7, clinical stage T1-T2, and prostate-specific antigen <20 ng/mL [to convert to micrograms per liter, multiply by 1.0]) diagnosed between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2014. For EBRT, only ≥75 Gy or ≥42 fractions of treatment were included. Stereotactic body radiation therapy was defined as 5 fractions of ≥7 Gy per fraction.

[..] A total of 12 864 patients (41.8%) received BT, 17 247 (56.1%) received DE-EBRT, and 655 (2.1%) received SBRT. From 2004 to 2014, SBRT use (0.03% to 10.6%) and DE-EBRT use (48.3% to 62.0%) steadily increased, with a corresponding decline in BT use (48.3% to 27.4%).

[..] The median follow-up was 6.7 years (range, 0-11.9 years). In the favorable intermediate risk cohort, there was no significant OS difference in pairwise comparisons of BT vs SBRT (HR, 0.804; 95% CI, 0.593-1.09; 10-year OS, 67.02% vs 64.2%) or SBRT vs DE-EBRT (HR, 1.096; 95% CI, 0.810-1.48; 10-year OS, 64.2% vs 70.9%). Men receiving BT had a small but statistically significant improvement in OS compared with those receiving DE-EBRT (HR, 0.881; 95% CI, 0.829-0.938; 10-year OS, 69.8% vs 66.1%).

In the unfavorable intermediate risk cohort, there were no OS differences in pairwise comparisons between BT and SBRT (HR, 0.749; 95% CI, 0.419-1.34; 10-year OS, 64.9% vs 63.2%) and between SBRT and DE-EBRT (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 0.746-2.69; 10-year OS, 63.2% vs 66.6%). Men receiving BT demonstrated a small but statistically significant improvement in OS compared with those receiving DE-EBRT (HR, 0.818; 95% CI, 0.716-0.936; 10-year OS, 61.2% vs 58.7%).

[..] This cohort study is a preliminary evaluation comparing outcomes of patients with intermediate-risk CaP, with results suggesting no difference in long-term survival between patients treated with SBRT, EBRT, or BT. These findings corroborate the results of the Hypofractionated Radiotherapy of Intermediate Risk Localised Prostate Cancer (HYPO-RT-PC) study demonstrating noninferior 5-year failure-free survival between ultrahypofractionated and conventionally fractionated therapy. Although BT has long been shown to be both clinically effective and cost-effective in the management of localized CaP, many studies, including the present study, show a decline in use over the last decade. As radiation modalities trend toward hypofractionation with major considerations toward cost-effective treatment, our preliminary evaluation suggests that SBRT and BT remain appropriate management strategies in delivering value-based care.”

Trends in Use and Comparison of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy, Brachytherapy, and Dose-Escalated External Beam Radiation Therapy for the Management of Localized, Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer Nguyen KA, Lee A, Patel SA et al. JAMA Network Open 2020.9.24

2020.9.23

“As the largest integrated and federally operated health care system in the US, the practice environment at the VHA differs considerably from other systems, potentially impacting the provision of low-value care. For example, VHA clinicians do not operate within a fee-for-service system and are insulated from malpractice litigation. Moreover, the VHA electronic medical record contains information on veterans’ care across all Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMCs) and decision support tools for ordering appropriate health services, which may be associated with a decreased likelihood of VA clinicians delivering low-value care.”

Low value diagnostic tests:

- Back imaging for patients with non-specific low back pain

- Head imaging for uncomplicated headache

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) for headaches

- Head imaging in patients with syncope

- Assessing for carotid artery disease in patients with syncope

- CT scan of the sinuses for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis

The researchers included reasonable filters to exclude clinically appropriate patients.

[end of appendix review.]

“When applying the sensitive criteria, overall and VAMC-level low-value testing frequency varied substantially across conditions: 18.2% (adjusted VAMC range, 10.9%-24.6%) for low back pain, 12.8% (range, 8.6%-22.6%) for headache, 20.1% (range, 16.3%-27.7%) for syncope, and 4.6% (range, 2.7%-10.1%) for sinusitis. With the specific criteria, the overall frequency of low-value testing across VAMCs was lower: 5.6% (range, 3.6%-7.7%) for low back pain, 8.6% (range, 6.2%-14.6%) for headache, 13.3% (range, 11.3%-16.8%) for syncope, and 2.4% (range, 1.3%-5.1%) for sinusitis. In veterans with a Gagne Comorbidity Score in the top decile and thus at greatest risk of mortality at 1-year, overall rates and ranges across VAMCs were similar to those demonstrated in the overall cohort when applying both the sensitive and specific criteria.

[..] Low-value testing for different conditions was significantly correlated at the VAMC level, with ρ values ranging from 0.18 (P = .04) for the correlation between syncope and sinusitis to 0.56 (P < .001) for the correlation between syncope and headache. When evaluating the correlation between the use of separate low-value tests for syncope, head imaging and carotid ultrasonography were significantly correlated when applying both the sensitive (ρ = 0.40; P < .001) and specific (ρ = 0.21; P = .02) criteria. For headache, use of head imaging and electroencephalography were significantly correlated when applying the sensitive criteria (ρ = 0.26, P = .003) but not when applying the specific criteria (ρ = 0.13, P = .16).

[..] In a national cohort of veterans, low-value diagnostic testing was common, affecting from 5% to 21% of veterans based on their underlying condition and similarly affecting those at greatest risk of 1-year mortality. We also identified 2- to 5-fold variation in low-value testing across VAMCs and significant correlation at the VAMC level in veterans’ receipt of such testing.

[..] Our findings are notable in that VA clinicians are not subject to the same incentives and circumstances commonly associated with low-value testing in non-VA settings in the US. [..] the variation that we observed in low-value testing across VAMCs could not be easily explained by the traditional veteran- and VAMC-level covariates that we incorporated in our analyses. This suggests that unique local factors, such as those related to provider culture and variations in the robustness of decision support for ordering tests and procedures at each VAMC, are associated with low-value testing. Similar factors may also play a role in other non-US health systems, such as Canada’s, where low-value care is broadly present despite operating largely within a single payer system. Identifying these factors will be essential for the development of interventions to reduce the delivery of such care in the VHA and other integrated health care systems.

The correlations of the receipt of low-value testing among the health conditions in our study also suggest that the delivery of such care at VAMCs is associated with systemic factors that are not specific to the delivery of an individual test.”

Evaluation of Low-Value Diagnostic Testing for 4 Common Conditions in the Veterans Health Administration Radornski TR, Feldman R, Huang YH et al. JAMA Network Open 2020.9.22

“Many institutions have focused on the proliferation of solutions and technologies supporting ambulatory care, along with health systems’ increasing focus on extending care along the continuum. Importantly, these trends will not dissipate soon, as they are driven by more fundamental, interrelated market changes:

1. Innovation and technology: Advances in clinical approaches and technology, including new developments in anesthesia and pain control, as well as minimally invasive surgical procedures, have enabled numerous procedures (for example, knee replacements, tonsillectomies) to migrate into the ambulatory setting.

3. Payer pressure: The growth of at-risk contracts and value-based care

4. Provider opportunity: Shared ownership models financially align physicians to accelerate this shift to outpatient care.

[..] We created a tool that analyzed a database of Commercial claims from across the United States in 2016. This database represented 1.4 billion national medical claims and more than $620 billion in cost. After excluding post-acute and other care, the claims were grouped together into 615 million encounters for ambulatory and inpatient care that represented $490 billion in cost. Each encounter was then given a priority procedure to enable comparisons to be made. Of the 615 million encounters, roughly 10 percent were coded as primarily surgical, 13 percent as primarily medical, and the remaining roughly 77 percent spanned office appointments, preventative care, and emergency department visits.